Difference between revisions of "Fitness Influencers"

(added another reference) |

(added another reference and some text) |

||

| Line 70: | Line 70: | ||

===== Before and After Photos ===== | ===== Before and After Photos ===== | ||

[[File:Beforeafter1.png|300px|thumbnail|right|An example of a before and after photo: Jenna Jameson's keto diet transformation.<ref>Wischhover, C. (2019, February 20). Why we can't look away from before-and-after pictures. Vox. https://www.vox.com/the-goods/2019/2/20/18226699/jenna-jameson-keto-diet-weight-loss-photos-before-and-after. </ref>]] | [[File:Beforeafter1.png|300px|thumbnail|right|An example of a before and after photo: Jenna Jameson's keto diet transformation.<ref>Wischhover, C. (2019, February 20). Why we can't look away from before-and-after pictures. Vox. https://www.vox.com/the-goods/2019/2/20/18226699/jenna-jameson-keto-diet-weight-loss-photos-before-and-after. </ref>]] | ||

| − | Photos of people before and after their fitness and weight loss journeys have been a way to show progress and promote fitness products since the 1980s. At first, they were primarily used to promote weight loss pills. They then were used as evidence in marketing for weight loss programs. They are used now to sell products as well as normalized as a way to celebrate physical body changes. Some people see these photos as an easy way to promote weight loss and exercise. When looked at in terms of how humans think and process information, before and after photos can be harmful. | + | Photos of people before and after their fitness and weight loss journeys have been a way to show progress and promote fitness products since the 1980s. At first, they were primarily used to promote weight loss pills. They then were used as evidence in marketing for weight loss programs. They are used now to sell products as well as normalized as a way to celebrate their physical body changes. Some people see these photos as an easy way to promote weight loss and exercise. When looked at in terms of how humans think and process information, before and after photos can be harmful. |

| − | It is human nature to compare and categorize new information, so people will use the phenomenon of [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_comparison_theory social comparison] to discover if they are closer to the “before” or “after” photo. These photos are meant to praise the weight loss and muscle gain of the “after” body, and they insinuate that the “before” body was less worthy than the new body. This causes people to evaluate their worthiness and believe they need to change. | + | It is human nature to compare and categorize new information, so people will use the phenomenon of [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_comparison_theory social comparison] to discover if they are closer to the “before” or “after” photo.<ref name=beforeandafter></ref> These photos are meant to praise the weight loss and muscle gain of the “after” body, and they insinuate that the “before” body was less worthy than the new body. They may be exciting for the person in the photos, but for viewers, it signals to them the need to change physically to be celebrated as a person. This causes people to evaluate their worthiness and believe they need to change.<ref>Jotanovic, D. (2021). Weight loss 'before and after' photos don't give us a full picture of our health.</ref> |

| − | These photos compare size with health. They make it seem like a leaner body is healthier, when that is not the case in every situation. The photos make aesthetic evidence for health when it is possible to be “healthy”, even if ones’ body does not look like an “after” photo. People can have good cardiovascular health, have good mental health, eat nutritious foods, have access to safe environments, and be happy without changing their physical appearance.<ref>Before and After Photos: Inspirational and Effective OR Demoralizing and Unethical? Precision Nutrition. (2020, August 10). https://www.precisionnutrition.com/before-and-after-photos. </ref> | + | These photos compare size with health. They make it seem like a leaner body is healthier, when that is not the case in every situation. The photos make aesthetic evidence for health when it is possible to be “healthy”, even if ones’ body does not look like an “after” photo. People can have good cardiovascular health, have good mental health, eat nutritious foods, have access to safe environments, and be happy without changing their physical appearance.<ref name=beforeandafter>Before and After Photos: Inspirational and Effective OR Demoralizing and Unethical? Precision Nutrition. (2020, August 10). https://www.precisionnutrition.com/before-and-after-photos. </ref> |

====Body Positivity==== | ====Body Positivity==== | ||

Revision as of 23:23, 15 April 2021

Contents

Currently Editing - Morgan Tucker

Fitness influencers create content that revolves around fitness and health-related topics, such as exercise and nutrition, and have been criticized for their role in diet culture. Their follower counts range from a thousand to millions across multiple platforms, allowing them to reach masses of people with fitness information, pictures, and any other content they link to their account. [1] These influencers hold influential power over their followers and have benefits such as free branding, compensation posts, and commission from companies. Some of the fitness content posted on social media platforms has raised ethical concerns surrounding misinformation, body image, and more. [2][3]

Fitness influencers’ social media content typically includes workout examples, training tips, motivational advice, information on nutrition, recommendations for dieting plans, and recipes for healthy eating. This content often takes the form of pictures and videos of fitness influencers demonstrating certain exercises, describing workout plans, making their favorite recipes, and showing their toned physique. Popular platforms include Instagram, Youtube, and TikTok.

Information Accessibility

A personal trainer can cost between $30 and $100 per hour, and nutritionists can cost up to $100 an hour. [5][6] Social media platforms are often free for users, making it free to view content posted by fitness influencers. Social media also “provides an opportunity to reach and engage with young adults that may not otherwise seek out health professionals in more traditional settings.” [7]

Fitness influencers’ content is “designed to motivate people to exercise and pursue a healthier lifestyle” and “to inspire people to achieve their fitness and body goals.” [8] Through follower bases and the ability to spread information on social media (ex: someone can "tag friends in the comments in order to bring them to the post"), social media helps fitness influencers inspire and motivate masses of people with their knowledge and advice. [9]

Career Opportunities

Fitness influencers use social media as a self-branding tool; a way to build their public image and expand the reach of their platform. [11] Fitness influencers can turn their social media commitment into a job and get paid to post content.

Income

Influencers make money through affiliate marketing, which is when influencers promote a product and then get compensated in commission that is based on how many customers the influencer brings in. [12] Influencers make money in other ways such as display advertising, sponsored posts, and brand campaigns. [12] One social media platform in particular, TikTok, has a creator fund; the company pays creators directly for individual posts. The number of views and the level of engagement determine how much a creator gets paid for a particular post. [13] Influencers typically make between $4,000 and $50,000 a month. [12]

Brand Sponsorship

Sponsorship by a company brand builds a strong base for many social media fitness influencers. Some of the top companies using social media influencer marketing are the top companies in athletic apparel today, such as Nike, Lululemon, Gymshark, and FitBit. They connect themselves with influencers with many followers to promote their product. Nike and Lululemon have different images they promote to greatly influence those they choose to be an ambassador. Lululemon promotes to the everyday active community member while Nike promotes toward the professional athlete or frequent gym visitor. These companies have easy application processes for becoming a brand ambassador with what seem to be simple requirements. At Lululemon, their mantra is "Sweat, Grow, and Connect".[14] There are specific legal guidelines and agreements that must be signed that limit what can be said in these posts and how to address disclosure requirements. The full list of Federal Trade Commission Guidelines for Nike can be found here. Those that qualify as an ambassador and follow the specific guidelines and conditions may receive great payouts, free apparel, store discounts, workout development tools, networking opportunities, and commission on products sold through individual promotions.[15][14]

For companies, brand influencers are seen as a highly collaborative environment with global audiences and almost immediate response times. It also creates a "just like us" mentality that increases brand familiarity among general consumers. Research also concludes that brand advertisements that create a greater sense of intimacy perform better. [16]

Entrepreneurship Opportunities

Some fitness influencers launch their own brands of clothing, workout plans, diet plans, supplements, etc. While it is more common for a fitness influencer to be sponsored, some influencers find success with this method as it allows them to add a personalized touch to the industry and their followers.

Michelle Lewin

Popular fitness influencer Michelle Lewin lists her brand partnerships in her bio, with the first company listed being one0one 101, a company she created alongside her husband that sells workout clothes. [17]

Ethical Implications

Misinformation

Social media users with a large platform are able to become fitness influencers, and often are not required to have applicable health and fitness qualifications. [1] Fitness influencers may upload inaccurate or inauthentic information, intentionally or unintentionally. [18] For brand sponsorships, ethical issues about the quality and impact of the various products and programs that users promote is often brought into question, particularly that of "attractiveness, trustworthiness and expertise." [19]

Exercise Advice

Catherine Hiley's study of TikTok’s fitness content revealed that “27% of the videos that were analyzed demonstrated bad form or incorrect advice.” [20][21] The same study looked at a variety of specific exercises and calculated what percentage of influencers were teaching incorrect form in their descriptions or demonstrations of that particular exercise; this percentage ranged from 12% to 80%. [21] Users can learn incorrect form for different exercises if they try to imitate these such fitness influencers. [21] The audience of these users may be more susceptible to injury if they attempt to imitate incorrect form. [22][21]The inequitable access to professional trainers suggests that those in lower socioeconomic classes are more likely to face negative consequences from these ill equipped online instructors. The online visibility of certain fitness content creators are not entirely based on the merit of their knowledge. The site "Lean Minded" identified top fitness influencers and verified that many of them do not have actual certifications that suggest people should listen to their advice.[23]

Disordered Eating

Diet Advice

Some fitness influencers promote adhering to certain diets for a healthier lifestyle, such as ketogenic and vegan diets. [2] These diets are one-size-fits-all plans, assuming that the same dieting techniques are effective for everyone. [2] Many of these diets are also fad diets, which "is a weight loss diet that becomes very popular quickly, and then falls out of favour just as quickly.” [24] Fad diets can be accompanied by health issues, such as low energy and constipation. [25] Oftentimes with fad diets, “weight loss occurs too fast, most of the lost weight being water and muscle, not fat tissue.” [25]

Orthorexia

Orthorexia nervosa is an eating disorder that refers to a fixation on eating ‘proper food’ that is accompanied by excessive exercise and usually starts as a desire to achieve a goal, such as improved health, but eventually becomes what is considered a socially, physically and mentally disabling illness [26]. High rates of orthorexia nervosa have been found in populations who take an active interest in their health and body[27], such as fitness influencers and their followers. A study found that the prevalence of orthorexia among social media users following health food accounts was 49%, which is significantly higher than the general population [27]. It has been found that the healthy eating community on Instagram has a high prevalence of orthorexia symptoms, with results showing higher Instagram use being linked to increased symptoms [27].

It is common for fitness influencers to utilize their platforms to share information regarding meal plans, labeling certain foods or food groups as “good food” or “bad food.”[28] It has been discussed that this type of “fitness” or “influencer” lifestyle has created moral judgements regarding specific food groups, not based on the effects it may have on human rights or the environment, but how closely it matches an influencers guidelines to wellness, which are rarely based on scientific health information [29]. This type of rhetoric can give followers the impression that if they adjust their eating habits to match what they see on Instagram, they will look the same way that influencers do [28]. Many of these meals are extremely low calorie, some only being 300 calories, which can lead to followers restricting their food intake and undernourishing themselves in an attempt to match an influencer's lifestyle [28]. These findings highlight the possible negative implications that social media fitness influencers may have over hundreds of thousands of individuals [28].

"What I Eat in a Day" Videos

Appearance

Fitness influencers usually fit beauty standards and often showcase their fit physiques to attract followers and get people to try their workouts or diets. [2] These creators’ physical appearances may be due to factors other than nutrition and exercise. [30] Some people are genetically predisposed to having a certain body shape, or they artificially modify their body using steroids or surgery. [30] Posing, clothing choice, lighting, and editing are also contributing factors in how a person’s body appears online. People may assume that a fitness influencer’s physique can be attributed to the diets, exercise regimes, and products that they recommend, but, if an influencer’s appearance is actually impacted by other factors, social media users might falsely believe the influencer’s fitness advice to be more impactful on one’s physique than it really is. [2]

Female fitness influencers have been shown to place an increased focus on their feminine sensuality and expressing bodily freedom in order to gain traction on the internet. Methodologies to achieve this include an increased focus on gluteus maximus workouts and shape along with carefully selective clothing and camera angles. Research on influencer Juliana Salimeni's Instagram account concluded careful juxtaposition of her partially-exposed body in conjunction with product placement is used to achieve optimal endorsements. [16]

Body Image

Fitness influencers promote healthy lifestyles, but oftentimes fit into one ideal prototype of what a healthy person should look like. [8] This “model spokesperson does not account for the vast and diverse general public the message is reaching.” [8] Because these influencers are typically fit and attractive (the "ideal prototype"), people who feel like they are not as conventionally attractive might start to compare their bodies to those of the creators they see on their feeds. [8][3] This can be detrimental to one’s body image. The link between consistent social media use and negative body image has to do with appearance comparisons. [3] Comparing oneself to thin and attractive fitness influencers, can create unrealistic body goals and cause low self-confidence for those viewing their content. [32] Anyone using social media will come across fitness influencer at some point. It was found in a study by BMC Public Health that, "90% of the analyzed contributions show influencers with at least one exposed body part," meaning that nearly all content online by these influencers are showing their body off in most posts.[33]

The prevalence of ideal body images in the media, particularly in regards to fitness influencers, has an impact on peoples' body image concerns and the development of eating disorders and other harmful behaviors. Much of the research conducted on the impacts of this type of media engagement is focused on females and concluded engaging with this type of media led to poor sleep quality, low self‐esteem, increased anxiety and depression, low appearance satisfaction and negative mood, high risk of body dissatisfaction, and thinness obsession. Males also struggle with the ideal "V-shaped" body type that created similar psychological consequences that can result in behaviors such as taking muscle gaining pills or steroids, engaging in excessive exercise, or having cosmetic surgery to sculpture their bodies. [34]

Before and After Photos

Photos of people before and after their fitness and weight loss journeys have been a way to show progress and promote fitness products since the 1980s. At first, they were primarily used to promote weight loss pills. They then were used as evidence in marketing for weight loss programs. They are used now to sell products as well as normalized as a way to celebrate their physical body changes. Some people see these photos as an easy way to promote weight loss and exercise. When looked at in terms of how humans think and process information, before and after photos can be harmful.

It is human nature to compare and categorize new information, so people will use the phenomenon of social comparison to discover if they are closer to the “before” or “after” photo.[36] These photos are meant to praise the weight loss and muscle gain of the “after” body, and they insinuate that the “before” body was less worthy than the new body. They may be exciting for the person in the photos, but for viewers, it signals to them the need to change physically to be celebrated as a person. This causes people to evaluate their worthiness and believe they need to change.[37]

These photos compare size with health. They make it seem like a leaner body is healthier, when that is not the case in every situation. The photos make aesthetic evidence for health when it is possible to be “healthy”, even if ones’ body does not look like an “after” photo. People can have good cardiovascular health, have good mental health, eat nutritious foods, have access to safe environments, and be happy without changing their physical appearance.[36]

Body Positivity

Social media can be a toxic place, especially within the realm of fitness. There is some positive and uplifting content to be found. Many fitness influencers focus on showcasing their perfect self with their perfect bodies, which does not accurately depict who they really are. Instead they just show a misleading glimpse of their lives. There are also fitness influencers who promote body positivity. Body positivity is “the assertion that all people deserve to have a positive body image, regardless of how society and popular culture view ideal shape, size, and appearance.” [39] These influencers try to connect with their followers and show the human side of the fitness journey. They show their followers to love their body, prioritize happiness, and not to hold themselves to unrealistic beauty standards that other fitness influencers push onto them. [40]

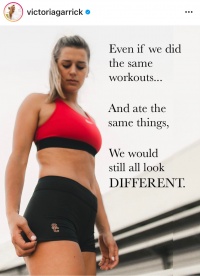

Star tennis player Serena Williams is involved in this group of influencers. She says, “I want women to know that it's okay. That you can be whatever size you are and you can be beautiful inside and out. We're always told what's beautiful, and what's not, and that's not right.” [41] This phenomena of body positivity goes beyond just famous athletes such as Serena Williams. There are other lesser known fitness influencers who also strongly support body positivity such as Victoria Garrick, who has about 275k followers on Instagram. As seen in the picture attached (screenshot from her Instagram account), she brings up a great point. Everybody has a different body that makes us unique and that should be embraced. Even if everybody worked out the same and ate the same, they would all have different bodies, which is extremely important to remember. All in all, the idea of body positivity is continuing to grow on social media and inspire people. It is important that this trend continues to make social media a more positive and accepting place, especially within the realm of fitness.

Capitalism

The influencer community includes people that will do and say things, whether they are true or not, to gain more of a following or make money. Some influencers care more about money than they do giving beneficial advice and evidence-based guidance.[42] The lack of transparency around the facts can negatively impact those looking up to this community. Fitness influencer advice is free to the users, so it should be called into question whether certain socioeconomic groups are being impacted disproportionately. These types of posts influence peoples' purchasing decisions, so consumers should be wary as to whether companies are buying the influencers they follow.[43]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Au-Yong-Oliveira, M., Cardoso, A. S., Goncalves, M., Tavares, A., & Branco, F. (2019). Strain Effect - A Case Study About the Power of Nano-Influencers. 2019 14th Iberian Conference on Information Systems and Technologies (CISTI). https://doi.org/10.23919/cisti.2019.8760911

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Lofft, Z. (2020). When social media met nutrition: How influencers spread misinformation, and why we believe them. Health Science Inquiry, 11(1), 56–61. https://doi.org/10.29173/hsi319

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Fardouly, J., & Vartanian, L. R. (2016). Social Media and Body Image Concerns: Current Research and Future Directions. Current Opinion in Psychology, 9, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.09.005

- ↑ Taylor, V. (2020, September 29). How to Start a Bomb Fitness Instagram Account (With Examples). wishpond. https://blog.wishpond.com/post/115675437921/how-to-start-a-fitness-instagram.

- ↑ Schnirring, L. (2015). Referring Patients to Personal Trainers: Benefits and Pitfalls. The Physician and Sportsmedicine, 28(1), 16–21. https://doi.org/10.3810/psm.2000.01.607

- ↑ Woodruff, M. (2012, January 2). The Cost Of Hiring A Dietitian. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/personal-finance/the-cost-of-hiring-a-dietician-2011-12.

- ↑ Klassen, K. M., Douglass, C. H., Brennan, L., Truby, H., & Lim, M. S. C. (2018). Social media use for nutrition outcomes in young adults: a mixed-methods systematic review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 15(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-018-0696-y

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Norton, M. (2017, May). Fitspiration: Social Media's Fitness Culture and its Effect on Body Image. Digital Commons @ CSUMB. https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C23&q=fitness+influencers+body+image&btnG=&httpsredir=1&article=1138&context=caps_thes_all.

- ↑ Noonan, M. (2018, June 21). Social Media Fitness Influencers: Innovators and Motivators. Iowa Research Online. https://ir.uiowa.edu/honors_theses/192.

- ↑ IZEA. (n.d.). Sponsored Instagram Posts. IZEA. https://izea.com/managed-services/influencer-marketing/sponsored-instagram-posts-2/.

- ↑ Khamis, S., Ang, L., & Welling, R. (2016). Self-branding, ‘micro-celebrity’ and the rise of Social Media Influencers. Celebrity Studies, 8(2), 191–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2016.1218292

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Heck, D., & Reed, C. (2020, February 4). How Do Influencers Make Money? Hecktic Media Inc. https://hmi.marketing/how-do-influencers-make-money/.

- ↑ TikTok. (2019, August 16). TikTok Creator Fund: Your questions answered. TikTok. https://newsroom.tiktok.com/en-gb/tiktok-creator-fund-your-questions-answered.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 “About the Program.” (2, April 2021) Lululemon, shop.lululemon.com/ambassadors/about-the-program.

- ↑ "Nike Brand Ambassador Program." (2, April 2021)Indi.com, https://indi.com/preview/a9cd7df6-b9ae-4ee2-8ac2-4488c8a7c8dc

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Silva, M. D. B., Farias, S. A., Grigg, M. H., & Barbosa, M. L. (2021). The body as a brand in social media: analyzing digital fitness influencers as product endorsers. Athenea Digital, 21(1), 1-34.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Davis, P. (2020, September 21). The 20 TOP fitness INFLUENCERS (+ how THEY SELF-PROMOTE). Retrieved April 02, 2021, from https://ampjar.com/blog/best-fitness-influencers/

- ↑ Sidhu, S. (2018). Social Media, Dietetic Practice and Misinformation: A triangulation research. Journal of Content, Community & Communication, 8, 29–34. https://doi.org/10.31620/JCCC.12.18/06

- ↑ Jason Weismueller, Paul Harrigan, Shasha Wang, Geoffrey N. Soutar,Influencer endorsements: How advertising disclosure and source credibility affect consumer purchase intention on social media, Australasian Marketing Journal (AMJ),Volume 28, Issue 4,2020,Pages 160-170,ISSN 1441-3582,https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ausmj.2020.03.002.

- ↑ Hosie, R. (2021, February 16). 5 red flags to look for before you take fitness advice from influencers. Yahoo! News. https://news.yahoo.com/5-red-flags-look-fitness-132254666.html.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 Hiley, C. (2021, February 1). The FitTok Report. money.co.uk. https://www.money.co.uk/mobiles/fittok-report.

- ↑ Gray, S. E., & Finch, C. F. (2015). The causes of injuries sustained at fitness facilities presenting to Victorian emergency departments - identifying the main culprits. Injury Epidemiology, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40621-015-0037-4

- ↑ LeanMinded, Mike Howard. “Under the Influencer: Why ‘Fitness Influencers’ Are Bad for Fitness and Humanity.” LeanMinded, https://leanminded.com/2019/04/16/under-the-influencer-why-fitness-influencers-are-bad-for-fitness-and-humanity/

- ↑ Crowe, T. (2014). Are fad diets worth their weight? Australasian Science. https://search.informit.org/doi/abs/10.3316/informit.508889208448431.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Khawandanah, J., & Tewfik, I. (2016). Fad Diets: Lifestyle Promises and Health Challenges. Journal of Food Research, 5(6), 80–94. https://doi.org/10.5539/jfr.v5n6p80

- ↑ “‘Wellness’ Lifts Us above the Food Chaos’: A Narrative Exploration of the Experiences and Conceptualisations of Orthorexia Nervosa through Online Social Media Forums.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 2018, www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/2159676X.2018.1464501?casa_token=-4dVoQkOse8AAAAA%3AlOAmmZ4CRCP2FgT8wzRmfztrzrIpgnbwIcrmPDCWYlaoEbe4qt2790mlIF81M-s5tlu7KK6tgJKJBA.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Turner, Pixie G., and Carmen E. Lefevre. “Instagram Use Is Linked to Increased Symptoms of Orthorexia Nervosa.” Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, vol. 22, no. 2, Mar. 2017, pp. 277–84, doi:10.1007/s40519-017-0364-2.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 Ao, Bethany. “How Instagram Creates ‘the Perfect Storm’ for Orthorexia, an Obsession with Healthy Eating.” Https://Www.inquirer.com, The Philadelphia Inquirer, 9 Mar. 2020, www.inquirer.com/health/wellness/orthorexia-eating-disorder-social-media-20200309.html.

- ↑ Thorpe, H. 2008. “Foucault, Technologies of Self, and the Media Discourses of Femininity in Snowboarding Culture.” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 32 (2): 199–229.10.1177/0193723508315206

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Schlossberg, M. (2016, July 23). The Dangers of Instagram Fitness. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/the-dangers-of-instagram-fitness-2016-7.

- ↑ JW Media, LLC. (2018, December 10). The 50 Best Fitness Influencers on Instagram. Muscle & Fitness. https://www.muscleandfitness.com/athletes-celebrities/girls/30-hottest-female-trainers-instagram/.

- ↑ Baranow, R. (2019, May 16). The impact of influencer marketing in the fitness industry on consumers’ trust. Modul Vienna University. https://www.modul.ac.at/uploads/files/Theses/Bachelor/Undergrad_2019/Thesis_1621022_BARANOW__Rebecca.pdf.

- ↑ Pilgrim, Katharina, and Sabine Bohnet-Joschko. “Selling Health and Happiness How Influencers Communicate on Instagram about Dieting and Exercise: Mixed Methods Research.” BMC Public Health, BioMed Central, 6 Aug. 2019, https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-019-7387-8

- ↑ Chatzopoulou, E., Filieri, R., & Dogruyol, S. A. (2020). Instagram and body image: Motivation to conform to the “Instabod” and consequences on young male wellbeing. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 54(4), 1270-1297.

- ↑ Wischhover, C. (2019, February 20). Why we can't look away from before-and-after pictures. Vox. https://www.vox.com/the-goods/2019/2/20/18226699/jenna-jameson-keto-diet-weight-loss-photos-before-and-after.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Before and After Photos: Inspirational and Effective OR Demoralizing and Unethical? Precision Nutrition. (2020, August 10). https://www.precisionnutrition.com/before-and-after-photos.

- ↑ Jotanovic, D. (2021). Weight loss 'before and after' photos don't give us a full picture of our health.

- ↑ "Garrick, Victoria. Instagram, 6 Oct. 2020, www.instagram.com/p/CGBUGiKlrKs/?igshid=sjl5sm87vjce.

- ↑ Cherry, Kendra. “What Is Body Positivity?” Verywell Mind, 21 Nov. 2020, www.verywellmind.com/what-is-body-positivity-4773402.

- ↑ Jennings, Rebecca. “The Paradox of Online ‘Body Positivity.’” Vox, Vox, 13 Jan. 2021, www.vox.com/the-goods/22226997/body-positivity-instagram-tiktok-fatphobia-social-media.

- ↑ Nuñez, Alanna. “Serena Williams' Top Five Body Image Quotes.” Shape, 21 June 2011, www.shape.com/celebrities/serena-williams-top-five-body-image-quotes.

- ↑ Duplaga, Mariusz. “The Use of Fitness Influencers’ Websites by Young Adult Women: A Cross-Sectional Study.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 17, no. 17, 2020, p. 6360.

- ↑ Arnold, Andrew. “Fitspiration On Social Media: Is It Helping Or Hurting Your Health Goals?” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 27 Dec. 2018, www.forbes.com/sites/andrewarnold/2018/11/26/fitspiration-on-social-media-is-it-helping-or-hurting-your-health-goals/?sh=232e78fa47f0.