Difference between revisions of "SNAP and Other Federal Nutrition Programs"

(→Failure to Meet Needs) |

(→Health Impacts) |

||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

===Health Impacts=== | ===Health Impacts=== | ||

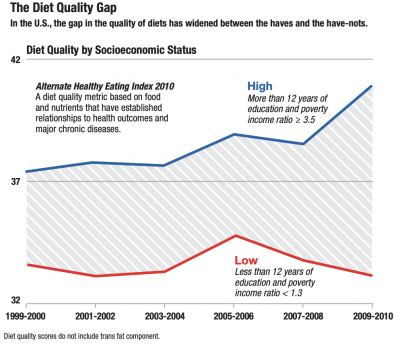

[[File:Haase5.png|400px|right|thumb|Gap in diet quality by socioeconomic status. https://www.heart.org/idc/groups/heart-public/@wcm/@adv/documents/downloadable/ucm_492637.pdf]] | [[File:Haase5.png|400px|right|thumb|Gap in diet quality by socioeconomic status. https://www.heart.org/idc/groups/heart-public/@wcm/@adv/documents/downloadable/ucm_492637.pdf]] | ||

| − | Determination from this information technology has ethical implications on the health and well-being of individuals. Failure to meet qualifications for SNAP and other federal nutrition programs means that many individuals have to make the most of their money by skipping meals, buying the cheapest (processed) foods, and not having the support to purchase more expensive fresh foods such as fruits and vegetables. <ref name=KathrynVasel></ref> The current benefit maximum allotment is 115% of the June 2020 value of the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thrifty_Food_Plan Thrifty Food Plan (TFP)], which is roughly $45 per week for males and $40 per week for females. <ref name=tfp>[https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/media/file/CostofFoodJun2020.pdf Official USDA Food Plans: Cost of Food at Home at Four Levels, U.S. Average, June 2020 1] United States Department of Agriculture </ref> | + | Determination from this information technology has ethical implications on the health and well-being of individuals. Failure to meet qualifications for SNAP and other federal nutrition programs means that many individuals have to make the most of their money by skipping meals, buying the cheapest (processed) foods, and not having the support to purchase more expensive fresh foods such as fruits and vegetables. <ref name=KathrynVasel></ref> The current benefit maximum allotment is 115% of the June 2020 value of the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thrifty_Food_Plan Thrifty Food Plan (TFP)], which is roughly $45 per week for males and $40 per week for females. <ref name=tfp>(July, 2020).[https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/media/file/CostofFoodJun2020.pdf Official USDA Food Plans: Cost of Food at Home at Four Levels, U.S. Average, June 2020 1]. United States Department of Agriculture.</ref> |

A review of 27 studies in 10 countries including the United States found that unhealthy food is on average $1.50 cheaper per day than healthy food. <ref name=rao>Rao, Mayuree, et. al. [https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/3/12/e004277 "Do healthier foods and diet patterns cost more than less healthy options? A systematic review and meta-analysis"] (BMJ Journals, Accessed March 11, 2021)</ref> Given the relative cost of processed and “healthy” foods, it is easier to meet daily nutritional needs by spending this little amount of money on processed foods. These cheaper foods are less nutritious than the latter and can put individuals at higher risks for health problems. <ref name=rao></ref> Davis' research has shown that the Thrifty Food Plan does not consider labor cost and is thus inadequate. <ref name=Davis> George C. Davis, Wen You, [https://academic.oup.com/jn/article/140/4/854/4743306 The Thrifty Food Plan Is Not Thrifty When Labor Cost Is Considered], The Journal of Nutrition, Volume 140, Issue 4, April 2010, Pages 854–857</ref> Using a basic labor economics technique, the study determined that with labor included, the mean household falls short of the TFP health guidelines even with the determined monetary resources. <ref name=Davis></ref> Children living in low-income families have worse health outcomes on average than other children on a number of indicators such as obesity and mental health. <ref name=Gupta> Gupta, Rita Paul-Sen et al. “The impact of poverty on the current and future health status of children” Pediatrics & child health vol. 12,8 (2007): 667-72. doi:10.1093/pch/12.8.667</ref> These negative health correlations with poverty levels are extended from information technologies such as these federal nutrition support programs. | A review of 27 studies in 10 countries including the United States found that unhealthy food is on average $1.50 cheaper per day than healthy food. <ref name=rao>Rao, Mayuree, et. al. [https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/3/12/e004277 "Do healthier foods and diet patterns cost more than less healthy options? A systematic review and meta-analysis"] (BMJ Journals, Accessed March 11, 2021)</ref> Given the relative cost of processed and “healthy” foods, it is easier to meet daily nutritional needs by spending this little amount of money on processed foods. These cheaper foods are less nutritious than the latter and can put individuals at higher risks for health problems. <ref name=rao></ref> Davis' research has shown that the Thrifty Food Plan does not consider labor cost and is thus inadequate. <ref name=Davis> George C. Davis, Wen You, [https://academic.oup.com/jn/article/140/4/854/4743306 The Thrifty Food Plan Is Not Thrifty When Labor Cost Is Considered], The Journal of Nutrition, Volume 140, Issue 4, April 2010, Pages 854–857</ref> Using a basic labor economics technique, the study determined that with labor included, the mean household falls short of the TFP health guidelines even with the determined monetary resources. <ref name=Davis></ref> Children living in low-income families have worse health outcomes on average than other children on a number of indicators such as obesity and mental health. <ref name=Gupta> Gupta, Rita Paul-Sen et al. “The impact of poverty on the current and future health status of children” Pediatrics & child health vol. 12,8 (2007): 667-72. doi:10.1093/pch/12.8.667</ref> These negative health correlations with poverty levels are extended from information technologies such as these federal nutrition support programs. | ||

Revision as of 18:08, 11 March 2021

There are many federal nutrition programs within the United States that aim to increase food access to individuals in need. One of the most prominent such programs is the United States Department of Agriculture United States Department of Agriculture Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), formerly known as Food Stamps, which provides monetary nutrition benefits to supplement food budgets of families in need to move towards self-sufficiency. This program reached 38 million people nationwide in 2019, of which more than 66% were in families with children; average monthly SNAP benefits for each household member ranged from $100-200 depending on location. [1] This program and other similar federal nutrition programs can be understood as an information technology because it uses a mass formula which is an algorithm that could be automated to determine individual and family eligibility.

Contents

Overview

Eligibility

The determination of eligibility follows a set of strict federal rules.[2] To be eligible for benefits, a household’s income and resources must meet three core criteria: gross monthly income must be at or below 130 percent of the poverty line, net income must be at or below the poverty line, and assets must fall below certain limits. Additionally, there are certain groups of people who are not eligible for SNAP benefits regardless of their income, including individuals on strike, unauthorized immigrants, and some lawfully present immigrants. [2] The mass formula for determining eligibility skips people that do not qualify numerically.

A Note on COVID-19

Until January 16, 2021 with the introduction of the Consolidated Appropriations Act 2021, students in college were not eligible for SNAP benefits [3] -- some eligibility rules were temporarily expanded during COVID-19, lasting until September 30, 2021. [3] This act temporarily expanded eligibility to higher education students if they meet one of two specific new criteria. [3] Prior to this change many students had to look elsewhere for food assistance.

During the pandemic, avoiding public areas such as grocery stores is important when individuals have pre-existing conditions. The United States Center for Disease Control recommends with evidence avoiding public spaces to limit risk of exposure to COVID-19. [4] Many people have to rely on grocery delivery services, and very few online grocery delivery services will accept SNAP payments. [5] This difficulty in using SNAP benefits during COVID-19 raises food security concerns for many individuals. [5]

Ethical Concerns

Failure to Meet Needs

There are many cases of individuals and families in need of food that do not qualify for SNAP based on the mass formula algorithm. More than 41 million people are "food insecure", meaning that they do not have consistent access to adequate food, and roughly 1 in 4 of these individuals are not likely to be eligible for programs such as SNAP. [6] Having these hard guidelines for eligibility means that there are some cases where individuals miss the qualification by a few dollars over the limit. [6] Additionally many individuals that are on SNAP benefits struggle to make ends meet with the small allotment decided upon. Despite the algorithm determining they have sufficient funds, NPR gives specific examples of individuals with food security struggles. [5]

Due to changes in congressional power and presidency, there are amendments made to the existing eligibility requirements. One of the more recent changes cut off an estimated 700,000 unemployed people from food assistance provided by SNAP. [7] This change targeted a group of people known as able-bodied adults without dependents. Taking support from some of those individuals can harm more than just them -- many of those people share their benefits with family or their social network and can create a ripple-effect from these cuts.

Decision Power

Bias in information systems also can exist within public services, not just private corporations. There are deep historical roots of biases against the poor that characterize today’s “tools of digital poverty management”. [8] These biases, harmful or not, are ingrained in information technologies and their corresponding algorithms. Such algorithms can have tremendous impacts on individual’s lives and the social aids they receive -- they can determine who is at risk of child abuse, who is best suited for a given job, and in this case, who is eligible for “food stamps”.

These federal nutrition programs can be thought of in context of a “weapon of math destruction”. Cathy O’Neil, coiner of this term, says that these WMDs can combine data injustice and systemic inequality to trap poor people in negative “feedback loops”. [9] O'Neil says math is demonstrated to be not only entangled in the world’s problems, but also fueling them, [9] and this math determines which which individuals qualify for social benefits. Numbers such as income and assets can be the difference between “food insecure” and food security.

Health Impacts

Determination from this information technology has ethical implications on the health and well-being of individuals. Failure to meet qualifications for SNAP and other federal nutrition programs means that many individuals have to make the most of their money by skipping meals, buying the cheapest (processed) foods, and not having the support to purchase more expensive fresh foods such as fruits and vegetables. [6] The current benefit maximum allotment is 115% of the June 2020 value of the Thrifty Food Plan (TFP), which is roughly $45 per week for males and $40 per week for females. [10]

A review of 27 studies in 10 countries including the United States found that unhealthy food is on average $1.50 cheaper per day than healthy food. [11] Given the relative cost of processed and “healthy” foods, it is easier to meet daily nutritional needs by spending this little amount of money on processed foods. These cheaper foods are less nutritious than the latter and can put individuals at higher risks for health problems. [11] Davis' research has shown that the Thrifty Food Plan does not consider labor cost and is thus inadequate. [12] Using a basic labor economics technique, the study determined that with labor included, the mean household falls short of the TFP health guidelines even with the determined monetary resources. [12] Children living in low-income families have worse health outcomes on average than other children on a number of indicators such as obesity and mental health. [13] These negative health correlations with poverty levels are extended from information technologies such as these federal nutrition support programs.

References

- ↑ Hall, L. (Jan. 12, 2021). “A Closer Look at Who Benefits from SNAP: State-by-State Fact Sheets”. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 (Sept. 01, 2020).“A Quick Guide to SNAP Eligibility and Benefits”. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 (March 3, 2021). Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program: Students. United States Department of Agriculture.

- ↑ (October 28, 2020). Deciding To Go Out. United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Gingold, Naomi. (April 30, 2020).“Coronavirus Pandemic Complicates Getting Groceries with SNAP”. NPR.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Vasel, Kathryn. (May 30, 2018). “Too poor to afford food, too rich to qualify for help”. CNN Business.

- ↑ Dickinson, Maggie. (December 10, 2019). The Ripple Effects of Taking SNAP Benefits From One Person. The Atlantic.

- ↑ Eubanks, V. (2017). Chapter 1 From Poorhouse to database. In Automating Inequality. NY: St. Martin’s Press.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 O’Neil, C. (2016). Introduction. In Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy. New York: Crown Publishing Group.

- ↑ (July, 2020).Official USDA Food Plans: Cost of Food at Home at Four Levels, U.S. Average, June 2020 1. United States Department of Agriculture.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Rao, Mayuree, et. al. "Do healthier foods and diet patterns cost more than less healthy options? A systematic review and meta-analysis" (BMJ Journals, Accessed March 11, 2021)

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 George C. Davis, Wen You, The Thrifty Food Plan Is Not Thrifty When Labor Cost Is Considered, The Journal of Nutrition, Volume 140, Issue 4, April 2010, Pages 854–857

- ↑ Gupta, Rita Paul-Sen et al. “The impact of poverty on the current and future health status of children” Pediatrics & child health vol. 12,8 (2007): 667-72. doi:10.1093/pch/12.8.667