Difference between revisions of "Right to be Forgotten"

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | The '''right to be forgotten''', also known as the right to erasure, is the right of an individual to erase parts of their [[Online Identity|online identity]] that include personal information which is no longer needed for its original processing purpose. The right to be forgotten has two parts. The first part | + | The '''right to be forgotten''', also known as the right to erasure, is the right of an individual to erase parts of their [[Online Identity|online identity]] that include personal information which is no longer needed for its original processing purpose. The right to be forgotten has two parts. The first part or the original intent of the right to be forgotten refers to the erasure of criminal records of criminals who have served their time and would like to erase the digital footprint of the criminal records. The second part of the right to be forgotten pertains to individuals who would like to remove personal information released through passive disclosure from the digital landscape. Both aspects of the right stem from the idea that individuals should be able to control whether or not their information exists online.<ref name = "Meg">Meg Leta Ambrose, and Jef Ausloos. “The Right to Be Forgotten Across the Pond.” Journal of Information Policy, vol. 3, 2013, pp. 1–23. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.5325/jinfopoli.3.2013.0001.</ref> The primary concern for these individuals is the persistence of information that is damaging to their online image. In the European Union (EU) and Argentina, this right has already been implemented with the creation of laws allowing citizens to request that their information be removed from [[Google|Google's]] search results. A noticeable trend among individuals requesting to be forgotten online is the recognition that they have paid their time, and therefore should no longer be linked to certain information. The right to be forgotten highlights the tension between access to information and the right to [[Privacy in the Online Environment|privacy]], as well as online anonymity problems. |

[[File:DELETE_PAST.jpg|right|thumb|250px]] | [[File:DELETE_PAST.jpg|right|thumb|250px]] | ||

| Line 36: | Line 36: | ||

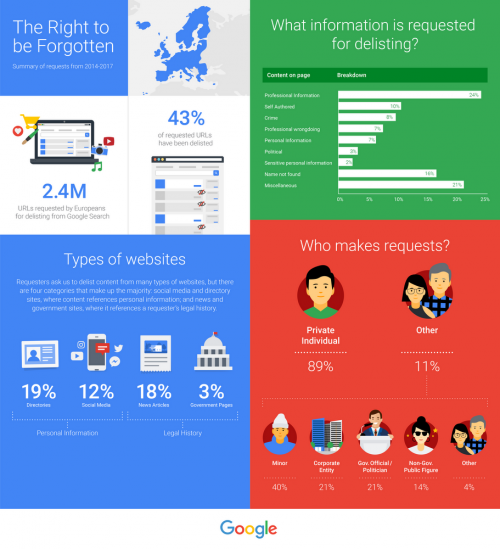

Google gathered and categorized data about all of the delisting requests which Europeans made from 2014-2017. The infographic below shows in detail the summary of the people who exercised their right to be forgotten as well as the information requested for delisting.<ref name=GoogleReport> Michee Smith, [https://www.blog.google/around-the-globe/google-europe/updating-our-right-be-forgotten-transparency-report/ "Updating our “right to be forgotten” Transparency Report"]. Google Inc., 26 February 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2019.</ref> | Google gathered and categorized data about all of the delisting requests which Europeans made from 2014-2017. The infographic below shows in detail the summary of the people who exercised their right to be forgotten as well as the information requested for delisting.<ref name=GoogleReport> Michee Smith, [https://www.blog.google/around-the-globe/google-europe/updating-our-right-be-forgotten-transparency-report/ "Updating our “right to be forgotten” Transparency Report"]. Google Inc., 26 February 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2019.</ref> | ||

| − | [[File:Rtbf.png| | + | [[File:Rtbf.png|right|thumb|500px|Google Transparency Report]] |

Google received 2.4 million requests from EU citizens for links to be removed from their indexes. A little less than half (43%) of the requested links were actually delisted by Google.<ref name=GoogleReport/> The categories of information that made up the majority of the delisting requests were professional information(24%), miscellaneous(21%), and name not found(16%).<ref name=GoogleReport/> On the other hand, the categories of information that were the least represented were sensitive personal information(2%), political(3%), and personal information(7%).<ref name=GoogleReport/> The four main types of websites that information was requested to be delisted from are directories(19%), news articles(18%), social media(12%), and government pages(3%).<ref name=GoogleReport/> Private individuals made up 89% of the removal requests while minors, corporate entities, and government politicians helped make up the majority of the remaining 11% of requests.<ref name=GoogleReport/> | Google received 2.4 million requests from EU citizens for links to be removed from their indexes. A little less than half (43%) of the requested links were actually delisted by Google.<ref name=GoogleReport/> The categories of information that made up the majority of the delisting requests were professional information(24%), miscellaneous(21%), and name not found(16%).<ref name=GoogleReport/> On the other hand, the categories of information that were the least represented were sensitive personal information(2%), political(3%), and personal information(7%).<ref name=GoogleReport/> The four main types of websites that information was requested to be delisted from are directories(19%), news articles(18%), social media(12%), and government pages(3%).<ref name=GoogleReport/> Private individuals made up 89% of the removal requests while minors, corporate entities, and government politicians helped make up the majority of the remaining 11% of requests.<ref name=GoogleReport/> | ||

| Line 42: | Line 42: | ||

==Ethical Issues== | ==Ethical Issues== | ||

According to [[James H. Moor|Moor's]] Law: "As technological revolutions increase their social impact, ethical problems increase."<ref> James H. Moor, [https://crown.ucsc.edu/academics/pdf-docs/moor-article.pdf "Why we need better ethics for emerging technologies"]. Ethics and Information Technology (2005) 7:111–119. Retrieved 12 March 2019.</ref> The right to be forgotten has arisen as an ethical issue due to the availability of information and ease of access that the internet has provided. While the European Union and Argentina have laws set in place protecting the right to be forgotten, the United States and many other countries have no such protections. These differences spark the debate over whether or not each country should create a law for the right to be forgotten. The main ethical issue concerning the right to be forgotten is the clash between the [[Freedom of Expression|freedom of expression]] and the right to privacy. | According to [[James H. Moor|Moor's]] Law: "As technological revolutions increase their social impact, ethical problems increase."<ref> James H. Moor, [https://crown.ucsc.edu/academics/pdf-docs/moor-article.pdf "Why we need better ethics for emerging technologies"]. Ethics and Information Technology (2005) 7:111–119. Retrieved 12 March 2019.</ref> The right to be forgotten has arisen as an ethical issue due to the availability of information and ease of access that the internet has provided. While the European Union and Argentina have laws set in place protecting the right to be forgotten, the United States and many other countries have no such protections. These differences spark the debate over whether or not each country should create a law for the right to be forgotten. The main ethical issue concerning the right to be forgotten is the clash between the [[Freedom of Expression|freedom of expression]] and the right to privacy. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | In opposition, advocates for the right to privacy believe that data divulged privately which is made public in some way should be removed immediately as the subject has the right to privacy of their information. [[Luciano Floridi]] defines the right to informational privacy as “the freedom from informational interference or intrusion, achieved through a restriction of facts about oneself that are unknown or unknowable.” <ref> Luciano Floridi, [https://umich.instructure.com/courses/273552/files/9617533?module_item_id=590872 The 4th Revolution] Chapter 5. Oxford University Press, 2014. Retrieved 11 March 2019.</ref> Thus they believe that the publication of this information is a violation of the right to privacy and therefore subject at hand should have the right to be forgotten without violating the freedom of expression.<ref> Ivor Shapiro [https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2016.1239545 "How the “Right to be Forgotten” Challenges Journalistic Principles"]. Digital Journalism Volume 5, 2017. Retrieved 14 March 2019.</ref> | + | ===Freedom of Expression=== |

| + | Advocates for the [http://si410wiki.sites.uofmhosting.net/index.php/Freedom_of_Expression freedom of expression] believe that subjects invoke the right to be forgotten simply when their content no longer suits their needs.<ref name=Freedom> Muge Fazlioglu, [http://dx.doi.org.proxy.lib.umich.edu/10.1093/idpl/ipt010 "Forget me not: the clash of the right to be forgotten and freedom of expression on the Internet"]. International Data Privacy Law; Oxford Vol. 3, Iss. 3, (Aug 2013): 149 - 157. Retrieved 14 March 2019.</ref> Furthermore, they claim that citizens who request the removal of information that was lawfully published by a website are directly violating the freedom of expression of that website. When a user removes information about themselves which could hurt their reputation, they are restricting the access of information for the public.<ref name=Freedom/>. Due to the case by case nature of the right to be forgotten, the line between the freedom of expression and right to privacy varies with each decision the search engine makes. This thus makes the ethical dilemma more clouded as the various requests for delisting can be very different. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Privacy=== | ||

| + | In opposition, advocates for the right to privacy believe that data divulged privately which is made public in some way should be removed immediately as the subject has the right to privacy of their information. [[Luciano Floridi]] defines the right to informational privacy as “the freedom from informational interference or intrusion, achieved through a restriction of facts about oneself that are unknown or unknowable.” <ref> Luciano Floridi, [https://umich.instructure.com/courses/273552/files/9617533?module_item_id=590872 The 4th Revolution] Chapter 5. Oxford University Press, 2014. Retrieved 11 March 2019.</ref> The ability to create and maintain meaningful relationships and benefit from these relationships is determined by our control over ourselves and access to information about ourselves<ref name=Rachels>Rachels, J. 1975. ”Why Privacy Is Important”. http://public.callutheran.edu/~chenxi/Phil315_062.pdf</ref>. Different types of relationships are affected by certain bits of information that are either shared or withheld in varying amounts or degrees. Invasions of privacy can hinder or inhibit the ability for a person to sustain these types of healthy emotional relationships. Particularly online, which is a space where many relationships are maintained. The loss of privacy can also take away someone’s ability to communicate information about themselves exclusively and selectively to someone else. If one’s personal information is being spread through a media outlet, one cannot control the information that is being portrayed about them. Thus they believe that the publication of this information is a violation of the right to privacy and therefore subject at hand should have the right to be forgotten without violating the freedom of expression.<ref> Ivor Shapiro [https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2016.1239545 "How the “Right to be Forgotten” Challenges Journalistic Principles"]. Digital Journalism Volume 5, 2017. Retrieved 14 March 2019.</ref> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

*'''Children & the Right to be Forgotten''' - Many parents like to showcase their children's experiences and accomplishments on their social media profiles to keep friends and family updated. "Sharenting" is a term that has been coined to describe the intersection between a parent's right to share about their children and a child's right to control their digital footprint. The right to be forgotten recognizes that certain information pertaining to individuals loses its value overtime. This can help protect a child's privacy because someone may no longer identify with the information that was shared by their parents years prior and thus, ask Google to hide results from their search algorithms. <ref>Steinberg, S. 2018. How Europe’s ‘right to be forgotten’ could protect kids’ online privacy in the U.S.. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/parenting/wp/2018/07/11/how-europes-right-to-be-forgotten-could-protect-kids-online-privacy-in-the-u-s/?utm_term=.0f48dd39260e</ref> | *'''Children & the Right to be Forgotten''' - Many parents like to showcase their children's experiences and accomplishments on their social media profiles to keep friends and family updated. "Sharenting" is a term that has been coined to describe the intersection between a parent's right to share about their children and a child's right to control their digital footprint. The right to be forgotten recognizes that certain information pertaining to individuals loses its value overtime. This can help protect a child's privacy because someone may no longer identify with the information that was shared by their parents years prior and thus, ask Google to hide results from their search algorithms. <ref>Steinberg, S. 2018. How Europe’s ‘right to be forgotten’ could protect kids’ online privacy in the U.S.. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/parenting/wp/2018/07/11/how-europes-right-to-be-forgotten-could-protect-kids-online-privacy-in-the-u-s/?utm_term=.0f48dd39260e</ref> | ||

| − | === | + | ===Entailment and Personal Harm=== |

| − | + | Supporters of the Right to be Forgotten argue that it should be included under their right to privacy. That is, people should have the right to control what information exists about them on the internet and should have autonomy over the creation and deletion of such information.<ref name=Arguments/> The argument follows that the right to privacy is a "moral right" which is granted in the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights. <ref> [https://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/ "Universal Declaration of Human Rights"]. United Nations, 10 December 1948. Retrieved 29 March 2019. </ref> The assumption is made that the right to privacy, or the right to control ones personal information, isn't complete without the right to be forgotten and therefore it is necessary to avoid psychological harm as well as potential physical harm.<ref name=Arguments/> Without the right to be forgotten, psychological harm can be caused by the posting of "inappropriate" personal information and physical harm can be caused by sensitive information remaining online which can have physical impacts in daily lives.<ref name=Arguments/> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ===No Content/No Responsibility=== | |

| − | + | In opposition to the Right to be Forgotten, the no content/no responsibility argument is based on the idea that Google and other search engines simply provide links to other content and therefore should not be held responsible for the content within the sites which they link to.<ref name=Arguments/> Those in opposition believe that the right to be forgotten unreasonably forces these search engines to filter their content based on delisting requests. Therefore the argument follows that since search engines provide no content, they should have no responsibility in regulating their links and should not be held accountable for the deletion of such content. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ===Fatigue/No Rest=== | |

| − | The public harm argument makes the assumption that the public has the inherent "right to know" and deals heavily with the ethics surrounding censorship benefits and censorship harms.<ref name=Arguments/> Those supporting this argument claim that limiting access to personal data goes against the notion of "free flow of information" and the allowance of one type of censorship will create a chain reaction of other types of censorship in online atmospheres. Those in opposition believe that the right to be forgotten will restrict the public's "right to know" by | + | Similarly, the fatigue/no rest argument claims that it is impractical to handle all user removal link requests under the right to be forgotten, and it overloads search engines with removal requests making it extremely difficult for them to process them all in a timely manner. Similar to the no content/no responsibility argument, fatigue/no rest argument is based on the idea that search engines shouldn't be responsibly for reviewing all of the requests for delisting.<ref name=Arguments/> |

| − | + | ||

| − | The internet degradation argument is centered around the idea that the internet's overall quality will become "degraded" due to the removal of links | + | ===Public Harm=== |

| − | + | The public harm argument makes the assumption that the public has the inherent "right to know" and deals heavily with the ethics surrounding censorship benefits and censorship harms.<ref name=Arguments/> Those supporting this argument claim that limiting access to personal data goes against the notion of "free flow of information" and the allowance of one type of censorship will create a chain reaction of other types of censorship in online atmospheres. Those in opposition believe that the right to be forgotten will restrict the public's "right to know" by removing links from search engines and thus cause overall harm to the general public as information is restricted. <ref name=Arguments/> | |

| + | |||

| + | ===Internet Degradation=== | ||

| + | The internet degradation argument is centered around the idea that the internet's overall quality will become "degraded" due to the removal of these links.<ref name=Arguments/> Those in opposition believe that the right to be forgotten allows for the increased removal of information online and thus degradation of the internet. The argument follows that the quality of content on the internet that can be beneficial to many users would be impaired. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Territoriality=== | ||

The international nature of the internet and search engines complicates the question of jurisdiction, and what laws and norms informational actors should follow. Luciano Floridi uses the phrase "My place, my rules v. your place, your rules" illustrate the role of geography in the ethics of the right to be forgotten<ref name= Luciano> Should You Have The Right To Be Forgotten On Google? Nationally, Yes. Globally, No. "2014"</ref>. When a search engine such as Google is used by millions of people in several different countries, it is difficult to regulate which information is restricted in which country, moreover, which search engine belongs to that particular country. For example, if an individual were to get a delink request approved to remove a specific piece of personal information in Europe, Google would remove the information from all European search engines. According to Floridi, this policy should be implemented as a more restricted, nation-based delinking policy<ref name= Luciano></ref>. He believes that by only removing the information from the country-specific Google search engine in which the request was made, the ability to have access to that specific piece of information in other countries is determined by the legislation of those other European countries. The "My place, my rules; Your place, your rules" saying is where this ideology stems from. Is it any one country's right to control the information that another country has access to? The argument of territoriality applies to the digital infosphere when considering the right to be forgotten. | The international nature of the internet and search engines complicates the question of jurisdiction, and what laws and norms informational actors should follow. Luciano Floridi uses the phrase "My place, my rules v. your place, your rules" illustrate the role of geography in the ethics of the right to be forgotten<ref name= Luciano> Should You Have The Right To Be Forgotten On Google? Nationally, Yes. Globally, No. "2014"</ref>. When a search engine such as Google is used by millions of people in several different countries, it is difficult to regulate which information is restricted in which country, moreover, which search engine belongs to that particular country. For example, if an individual were to get a delink request approved to remove a specific piece of personal information in Europe, Google would remove the information from all European search engines. According to Floridi, this policy should be implemented as a more restricted, nation-based delinking policy<ref name= Luciano></ref>. He believes that by only removing the information from the country-specific Google search engine in which the request was made, the ability to have access to that specific piece of information in other countries is determined by the legislation of those other European countries. The "My place, my rules; Your place, your rules" saying is where this ideology stems from. Is it any one country's right to control the information that another country has access to? The argument of territoriality applies to the digital infosphere when considering the right to be forgotten. | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | ===Publisher's Rights=== | ||

The publishers of legal information should also be considered. According to Luciano Floridi, argues that publishers should be heavily involved in the evaluation of the delinking process. This includes being notified when a person has requested to delink a piece of information that they legally published, being informed of the decision whether to allow the action of delinking or not, and appealing if they do not agree with this decision<ref name=Luciano></ref>. | The publishers of legal information should also be considered. According to Luciano Floridi, argues that publishers should be heavily involved in the evaluation of the delinking process. This includes being notified when a person has requested to delink a piece of information that they legally published, being informed of the decision whether to allow the action of delinking or not, and appealing if they do not agree with this decision<ref name=Luciano></ref>. | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | ===Censorship Concerns=== | ||

There are some concerns with allowing countries to make decisions about implementing the Right to be Forgotten outside of their own respective countries. In 2015 the Commission nationale de l’informatique et des libertés (CNIL) argued that it was not enough to just remove the information of citizens from French websites as people are able to access websites from other countries using a VPN or a similar service. <ref>Facebook.com/techpreviewindia. (2018, December 26). France tries to impose 'Right to be Forgotten' globally. Google fights. Retrieved from https://previewtech.net/right-to-be-forgotten-globally-google-cnil-france/</ref> Google argued that the law should reasonably be interpreted and countries should not be able to control the laws that govern this in other countries. Expunging information on topics on a global scale can turn into censorship when the information is of global interest. Being able to control the information available in other countries can and will most likely be misused especially when diplomacy becomes hostile. | There are some concerns with allowing countries to make decisions about implementing the Right to be Forgotten outside of their own respective countries. In 2015 the Commission nationale de l’informatique et des libertés (CNIL) argued that it was not enough to just remove the information of citizens from French websites as people are able to access websites from other countries using a VPN or a similar service. <ref>Facebook.com/techpreviewindia. (2018, December 26). France tries to impose 'Right to be Forgotten' globally. Google fights. Retrieved from https://previewtech.net/right-to-be-forgotten-globally-google-cnil-france/</ref> Google argued that the law should reasonably be interpreted and countries should not be able to control the laws that govern this in other countries. Expunging information on topics on a global scale can turn into censorship when the information is of global interest. Being able to control the information available in other countries can and will most likely be misused especially when diplomacy becomes hostile. | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

Revision as of 14:13, 23 April 2019

The right to be forgotten, also known as the right to erasure, is the right of an individual to erase parts of their online identity that include personal information which is no longer needed for its original processing purpose. The right to be forgotten has two parts. The first part or the original intent of the right to be forgotten refers to the erasure of criminal records of criminals who have served their time and would like to erase the digital footprint of the criminal records. The second part of the right to be forgotten pertains to individuals who would like to remove personal information released through passive disclosure from the digital landscape. Both aspects of the right stem from the idea that individuals should be able to control whether or not their information exists online.[1] The primary concern for these individuals is the persistence of information that is damaging to their online image. In the European Union (EU) and Argentina, this right has already been implemented with the creation of laws allowing citizens to request that their information be removed from Google's search results. A noticeable trend among individuals requesting to be forgotten online is the recognition that they have paid their time, and therefore should no longer be linked to certain information. The right to be forgotten highlights the tension between access to information and the right to privacy, as well as online anonymity problems.

History

Before the expansion of the internet and search engines such as Google and Yahoo, the right to be forgotten did not exist. In the Pre-internet era, data was not as easily accessible due to its physical nature and public records were difficult to obtain which lead to "practical obscurity" of people's data. This means that the data was effectively protected due to the practical difficulty required to access it.[2] As more records became digitized and digital libraries for search engines expanded, data became more easily accessible, leading to the question of whether people should be able to scrub their records. In 2010, the landmark case of Google vs. Costeja made the right to be forgotten a real possibility.

Google v. Costeja

In March 2010, a resident of Spain named Mario Costeja González filed a complaint against La Vanguardia newspaper regarding articles published online in 1998.[3] When Googling his name, Costeja obtained links to two articles from La Vanguardia which contained information about his forced sale of property in order to pay off social security debts.[4] Costeja requested that La Vanguardia remove this information from their site and also requested that Google remove these links from their search results. He believed that the sensitive information about his debts was damaging to his reputation even though those debts had previously been resolved and were no longer relevant.[4]

In July of 2010, the Agencia Española de Protección de Datos (AEPD) ruled that La Vanguardia legally had the right to publish this information about Costeja and therefore did not have to remove it.[3] However, the AEPD upheld the complaint which was directed at Google and ruled that the search engine had the obligation to remove the links to the newspaper articles from their indexes without necessarily erasing the data.

Following this ruling, Google took up claims against the Audiencia Nacional(National High Court of Spain) on the basis that Costeja didn't have the right to erase legally published material.[3] In 2014, the Court of Justice of the European Union ruled that search engines such as Google must respect the right to erasure. This landmark case resulted in a debate over the types of information that qualify for removal under the guidelines of the right to be forgotten. Ultimately, it lead to the publication of a form by Google which would allow citizens in the EU to request de-indexing of links that are no longer relevant to their original processing purpose.[5] Google handles the requests on a case by case basis and determines whether or not each request is eligible for the right to be forgotten.

Argentina

In Argentina, the lawyer Adolfo Martín Leguizamón Peña was filing similar cases for many celebrities against the search engines Google and Yahoo.[6] These celebrities demanded the removal of search results linked to photographs of themselves.

The most significant of the Argentinian cases, Da Cuhna v. Yahoo and Google, came about in 2009. In her lawsuit with the lower court, Virginia Da Cuhna of Argentina claimed that search results for her name resulted in links to pornographic websites which were using photographs of her without her permission. Judge Virginia Simari of Buenos Aires ruled in favor of Da Cuhna and claimed that she had a right to control her personal image online and Google and Yahoo were violating that right with their search results and therefore needed to remove links to pornographic sites which contained Da Cuhna's pictures.[6]

On appeal, a three-judge court reversed the lower courts decision on the grounds that the search engines could not be held accountable for linking to Da Cuhna's images as Da Cuhna had published them herself on her personal website. Although the judges reversed the decision, Judge Ana María R. Brilla de Serrat argued for the importance of the right to be forgotten along with the right to control information about oneself.[6] These cases helped to set a foundation for the right to be forgotten in Argentina.

United States of America

Currently, there are no legal frameworks in the United States protecting the right to be forgotten.

In 2014, a survey conducted by Benenson Strategy Group concluded that 88% of voters in the United States support the creation of a U.S. Law that would allow for citizens to request for the removal of personal information from search results.[7] Although such a large number of voters are in support of the creation of a right to be forgotten law in the U.S., the opposition claims that it would be a direct violation of the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. The First Amendment prohibiting Congress and the states from creating laws abridging the freedom of expression. [8] Advocates against the right to be forgotten in the U.S. claim that allowing individuals to remove some of their personal information online violates the freedom of expression of the publisher of that information. However, as is recognized in the Google v. Costeja, La Vanguardia was not forced to remove the article as it was published lawfully; Google only had to remove the link to the article. Because of this, some believe that by removing things from Google, no infringements are being made against speech or press since the information is technically still published, just no longer searchable.

There are currently frameworks in place that allow U.S. citizens to protect themselves from an invasion of privacy. If an individual feels they have experienced a breach in privacy due to their personal information being divulged inappropriately, they can legally request to get that information removed. [9] However, these laws don't encompass the right to be forgotten in the United States as they fail to protect the removal of personal information that was lawfully published online.[9]

In recent years, there have been a number of bills proposed concerning the right to be forgotten in the U.S., however, they have all been killed or remain pending in Congress.

European Union

The legal right to be forgotten, which was established in the Google v. Costeja case, was codified into the EU's General Data Protection Regulations, which are a set of comprehensive data protection and privacy laws that apply to all EU citizens. Article 17 of GDPR provides EU consumers the right to be forgotten, and to have their data erased by data controllers upon request. Article 19 obligates controllers to notify consumers when data erasures have been conducted.

GDPR establishes a consent-based data framework, whereby consumers can withdraw their consent at their desire, and thereby initiate the data erasure process. A data controller, which is the party that is responsible for managing consent and access rights, are statutorily required to comply with erasure requests. If the data has been copied and circulated to other controllers and processors or made the data public, the primary controller is responsible for notifying other parties of the data erasure. Data erasure is also required when the data is no longer necessary in relation to the purpose of why the data was primarily collected, or if it was originally collected unlawfully. All of these provisions provide consumers, as data subjects, the right to have their data erased when they want, or when the data is no longer needed in regards to the intent of its original collection. [10]

GDPR provides certain exceptions to the right to be forgotten provisions, so as not to unnecessarily overburden data controllers and processors, and create a over-regulated and hostile business environment. If data erasure requests violate individual or organizational first amendment rights, such as the freedom of speech and freedom of the press rights; the erasure request can be denied. Newspaper and media organizations, for example, are not required under GDPR to remove names and information of individuals in online articles, just because individuals submit an erasure request under GDPR provisions. These provisions primarily pertain to social media platforms, digital advertising networks, and platforms that monetize and commoditize online personalizes data. [11]

Google Transparency Report

Google gathered and categorized data about all of the delisting requests which Europeans made from 2014-2017. The infographic below shows in detail the summary of the people who exercised their right to be forgotten as well as the information requested for delisting.[12]

Google received 2.4 million requests from EU citizens for links to be removed from their indexes. A little less than half (43%) of the requested links were actually delisted by Google.[12] The categories of information that made up the majority of the delisting requests were professional information(24%), miscellaneous(21%), and name not found(16%).[12] On the other hand, the categories of information that were the least represented were sensitive personal information(2%), political(3%), and personal information(7%).[12] The four main types of websites that information was requested to be delisted from are directories(19%), news articles(18%), social media(12%), and government pages(3%).[12] Private individuals made up 89% of the removal requests while minors, corporate entities, and government politicians helped make up the majority of the remaining 11% of requests.[12]

Ethical Issues

According to Moor's Law: "As technological revolutions increase their social impact, ethical problems increase."[13] The right to be forgotten has arisen as an ethical issue due to the availability of information and ease of access that the internet has provided. While the European Union and Argentina have laws set in place protecting the right to be forgotten, the United States and many other countries have no such protections. These differences spark the debate over whether or not each country should create a law for the right to be forgotten. The main ethical issue concerning the right to be forgotten is the clash between the freedom of expression and the right to privacy.

Freedom of Expression

Advocates for the freedom of expression believe that subjects invoke the right to be forgotten simply when their content no longer suits their needs.[14] Furthermore, they claim that citizens who request the removal of information that was lawfully published by a website are directly violating the freedom of expression of that website. When a user removes information about themselves which could hurt their reputation, they are restricting the access of information for the public.[14]. Due to the case by case nature of the right to be forgotten, the line between the freedom of expression and right to privacy varies with each decision the search engine makes. This thus makes the ethical dilemma more clouded as the various requests for delisting can be very different.

Privacy

In opposition, advocates for the right to privacy believe that data divulged privately which is made public in some way should be removed immediately as the subject has the right to privacy of their information. Luciano Floridi defines the right to informational privacy as “the freedom from informational interference or intrusion, achieved through a restriction of facts about oneself that are unknown or unknowable.” [15] The ability to create and maintain meaningful relationships and benefit from these relationships is determined by our control over ourselves and access to information about ourselves[16]. Different types of relationships are affected by certain bits of information that are either shared or withheld in varying amounts or degrees. Invasions of privacy can hinder or inhibit the ability for a person to sustain these types of healthy emotional relationships. Particularly online, which is a space where many relationships are maintained. The loss of privacy can also take away someone’s ability to communicate information about themselves exclusively and selectively to someone else. If one’s personal information is being spread through a media outlet, one cannot control the information that is being portrayed about them. Thus they believe that the publication of this information is a violation of the right to privacy and therefore subject at hand should have the right to be forgotten without violating the freedom of expression.[17]

- Children & the Right to be Forgotten - Many parents like to showcase their children's experiences and accomplishments on their social media profiles to keep friends and family updated. "Sharenting" is a term that has been coined to describe the intersection between a parent's right to share about their children and a child's right to control their digital footprint. The right to be forgotten recognizes that certain information pertaining to individuals loses its value overtime. This can help protect a child's privacy because someone may no longer identify with the information that was shared by their parents years prior and thus, ask Google to hide results from their search algorithms. [18]

Entailment and Personal Harm

Supporters of the Right to be Forgotten argue that it should be included under their right to privacy. That is, people should have the right to control what information exists about them on the internet and should have autonomy over the creation and deletion of such information.[19] The argument follows that the right to privacy is a "moral right" which is granted in the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights. [20] The assumption is made that the right to privacy, or the right to control ones personal information, isn't complete without the right to be forgotten and therefore it is necessary to avoid psychological harm as well as potential physical harm.[19] Without the right to be forgotten, psychological harm can be caused by the posting of "inappropriate" personal information and physical harm can be caused by sensitive information remaining online which can have physical impacts in daily lives.[19]

No Content/No Responsibility

In opposition to the Right to be Forgotten, the no content/no responsibility argument is based on the idea that Google and other search engines simply provide links to other content and therefore should not be held responsible for the content within the sites which they link to.[19] Those in opposition believe that the right to be forgotten unreasonably forces these search engines to filter their content based on delisting requests. Therefore the argument follows that since search engines provide no content, they should have no responsibility in regulating their links and should not be held accountable for the deletion of such content.

Fatigue/No Rest

Similarly, the fatigue/no rest argument claims that it is impractical to handle all user removal link requests under the right to be forgotten, and it overloads search engines with removal requests making it extremely difficult for them to process them all in a timely manner. Similar to the no content/no responsibility argument, fatigue/no rest argument is based on the idea that search engines shouldn't be responsibly for reviewing all of the requests for delisting.[19]

Public Harm

The public harm argument makes the assumption that the public has the inherent "right to know" and deals heavily with the ethics surrounding censorship benefits and censorship harms.[19] Those supporting this argument claim that limiting access to personal data goes against the notion of "free flow of information" and the allowance of one type of censorship will create a chain reaction of other types of censorship in online atmospheres. Those in opposition believe that the right to be forgotten will restrict the public's "right to know" by removing links from search engines and thus cause overall harm to the general public as information is restricted. [19]

Internet Degradation

The internet degradation argument is centered around the idea that the internet's overall quality will become "degraded" due to the removal of these links.[19] Those in opposition believe that the right to be forgotten allows for the increased removal of information online and thus degradation of the internet. The argument follows that the quality of content on the internet that can be beneficial to many users would be impaired.

Territoriality

The international nature of the internet and search engines complicates the question of jurisdiction, and what laws and norms informational actors should follow. Luciano Floridi uses the phrase "My place, my rules v. your place, your rules" illustrate the role of geography in the ethics of the right to be forgotten[21]. When a search engine such as Google is used by millions of people in several different countries, it is difficult to regulate which information is restricted in which country, moreover, which search engine belongs to that particular country. For example, if an individual were to get a delink request approved to remove a specific piece of personal information in Europe, Google would remove the information from all European search engines. According to Floridi, this policy should be implemented as a more restricted, nation-based delinking policy[21]. He believes that by only removing the information from the country-specific Google search engine in which the request was made, the ability to have access to that specific piece of information in other countries is determined by the legislation of those other European countries. The "My place, my rules; Your place, your rules" saying is where this ideology stems from. Is it any one country's right to control the information that another country has access to? The argument of territoriality applies to the digital infosphere when considering the right to be forgotten.

Publisher's Rights

The publishers of legal information should also be considered. According to Luciano Floridi, argues that publishers should be heavily involved in the evaluation of the delinking process. This includes being notified when a person has requested to delink a piece of information that they legally published, being informed of the decision whether to allow the action of delinking or not, and appealing if they do not agree with this decision[21].

Censorship Concerns

There are some concerns with allowing countries to make decisions about implementing the Right to be Forgotten outside of their own respective countries. In 2015 the Commission nationale de l’informatique et des libertés (CNIL) argued that it was not enough to just remove the information of citizens from French websites as people are able to access websites from other countries using a VPN or a similar service. [22] Google argued that the law should reasonably be interpreted and countries should not be able to control the laws that govern this in other countries. Expunging information on topics on a global scale can turn into censorship when the information is of global interest. Being able to control the information available in other countries can and will most likely be misused especially when diplomacy becomes hostile.

References

- ↑ Meg Leta Ambrose, and Jef Ausloos. “The Right to Be Forgotten Across the Pond.” Journal of Information Policy, vol. 3, 2013, pp. 1–23. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.5325/jinfopoli.3.2013.0001.

- ↑ "Privacy and Public Records" epic.org. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Google Spain SL and Google Inc. v Agencia Española de Protección de Datos (AEPD) and Mario Costeja González. Case C‑131/12. Judgment of the Court (Grand Chamber), 13 May 2014. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Thomas Macaulay, "What is the right to be forgotten and where did it come from?. 14 September 2017. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ↑ Ignacio Cofone, "Google v. Spain: A Right To Be Forgotten". "15 Chi.-Kent J. Int'l & Comp. L.", 2015. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Edward L. Carter, "Argentina's Right to be Forgotten". Emory International Law Review Volume 27, 2013. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- ↑ Mario Trujillo, "Public wants 'right to be forgotten' online". Benenson Strategy Group. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- ↑ "U.S. Constitution-First Amendment". Legal Information Institute. Cornell Law School. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Leticia Bode & Meg Leta Jones, "Ready to forget: American attitudes toward the right to be forgotten". The Information Society, 8 March 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- ↑ "GDPR: Right to be Forgotten," Intersoft Consulting, https://gdpr-info.eu/issues/right-to-be-forgotten/

- ↑ "Do we always have to delete personal data if a person asks?" European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/law-topic/data-protection/reform/rules-business-and-organisations/dealing-citizens/do-we-always-have-delete-personal-data-if-person-asks_en

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 Michee Smith, "Updating our “right to be forgotten” Transparency Report". Google Inc., 26 February 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- ↑ James H. Moor, "Why we need better ethics for emerging technologies". Ethics and Information Technology (2005) 7:111–119. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Muge Fazlioglu, "Forget me not: the clash of the right to be forgotten and freedom of expression on the Internet". International Data Privacy Law; Oxford Vol. 3, Iss. 3, (Aug 2013): 149 - 157. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- ↑ Luciano Floridi, The 4th Revolution Chapter 5. Oxford University Press, 2014. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ↑ Rachels, J. 1975. ”Why Privacy Is Important”. http://public.callutheran.edu/~chenxi/Phil315_062.pdf

- ↑ Ivor Shapiro "How the “Right to be Forgotten” Challenges Journalistic Principles". Digital Journalism Volume 5, 2017. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- ↑ Steinberg, S. 2018. How Europe’s ‘right to be forgotten’ could protect kids’ online privacy in the U.S.. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/parenting/wp/2018/07/11/how-europes-right-to-be-forgotten-could-protect-kids-online-privacy-in-the-u-s/?utm_term=.0f48dd39260e

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedArguments - ↑ "Universal Declaration of Human Rights". United Nations, 10 December 1948. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Should You Have The Right To Be Forgotten On Google? Nationally, Yes. Globally, No. "2014"

- ↑ Facebook.com/techpreviewindia. (2018, December 26). France tries to impose 'Right to be Forgotten' globally. Google fights. Retrieved from https://previewtech.net/right-to-be-forgotten-globally-google-cnil-france/