Difference between revisions of "Facebook in Africa"

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

==Controversies== | ==Controversies== | ||

===Online Behavior=== | ===Online Behavior=== | ||

| − | Facebook and internet users in Africa have significantly less experience than users in America - with this comes the need to teach about digital etiquette. The idea of privacy, information transparency, fake news, digital embodiment are all foreign concepts to early internet users. The initial purpose according to Zuckerberg was to offer users “the opportunity to access news, health information and services for free.”<ref name=Shearlaw> Shearlaw, Maeve. Facebook Lures Africa with free internet – but what is the hidden cost? The Guardian. August 1st 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/aug/01/facebook-free-basics-internet-africa-mark-zuckerberg</ref> Zuckerberg himself believes that access to the internet is among our basic human rights, and that this access has the power to lift people out of poverty. <ref> Hempel, Jessi. “Facebook Renames Its Controversial Internet.org App.” Wired, Conde Nast, 29 June 2017, www.wired.com/2015/09/facebook-renames-controversial-internet-org-app/. </ref> While this may have been Zuckerberg's intentions, the reality is that user's are not receiving or searching for the information they need. Instead, users are considered passive consumers: Free Basics only offers them a small portion of information due to the restriction on sites provided by the service. When searching news, users will react to articles with clickbait headlines and not be able to fully sift through the news topic and obtain a well rounded view of the issue. For these types of users, fake news becomes a monumentous issue in Africa. As Frankfurt stated in his article “On Truth, Lies, and Bullshit” a lie is “designed to prevent us from being in touch with what is really going on.” <ref> Frankfurt, Harry. “On Truth, Lies, and Bullshit.” The Philosophy of Deception, by Clancy W. Martin, Oxford University Press, 2009.</ref> In this sense, Free Basics’s goal of providing clarity, information, and accessibility to a huge population of people can often backfire by causing users who are extremely uneducated in spotting fake news to believe falsities rather than find answers to news or health questions. In Frankfurt's eyes, these users were better off with their original ignorance rather than the lies or bullshit they found online. Furthermore as Africa is a continent where there are very few protections for digital privacy and laws about freedom of online expression, it has become a concern of many governments that Facebook is exploiting Africa’s lack of technical literacy to drive their business and profits. After failed efforts in Myanmar to protect users safety online, Facebook wrote that they were initially too “idealistic” in their efforts. They claim that moving forward they “have invested in people and technology to build better safeguards,” including fact-checking and support for digital literacy efforts around the globe. <ref | + | Facebook and internet users in Africa have significantly less experience than users in America - with this comes the need to teach about digital etiquette. The idea of privacy, information transparency, fake news, digital embodiment are all foreign concepts to early internet users. The initial purpose according to Zuckerberg was to offer users “the opportunity to access news, health information and services for free.”<ref name=Shearlaw> Shearlaw, Maeve. Facebook Lures Africa with free internet – but what is the hidden cost? The Guardian. August 1st 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/aug/01/facebook-free-basics-internet-africa-mark-zuckerberg</ref> Zuckerberg himself believes that access to the internet is among our basic human rights, and that this access has the power to lift people out of poverty. <ref> Hempel, Jessi. “Facebook Renames Its Controversial Internet.org App.” Wired, Conde Nast, 29 June 2017, www.wired.com/2015/09/facebook-renames-controversial-internet-org-app/. </ref> While this may have been Zuckerberg's intentions, the reality is that user's are not receiving or searching for the information they need. Instead, users are considered passive consumers: Free Basics only offers them a small portion of information due to the restriction on sites provided by the service. When searching news, users will react to articles with clickbait headlines and not be able to fully sift through the news topic and obtain a well rounded view of the issue. For these types of users, fake news becomes a monumentous issue in Africa. As Frankfurt stated in his article “On Truth, Lies, and Bullshit” a lie is “designed to prevent us from being in touch with what is really going on.” <ref> Frankfurt, Harry. “On Truth, Lies, and Bullshit.” The Philosophy of Deception, by Clancy W. Martin, Oxford University Press, 2009.</ref> In this sense, Free Basics’s goal of providing clarity, information, and accessibility to a huge population of people can often backfire by causing users who are extremely uneducated in spotting fake news to believe falsities rather than find answers to news or health questions. In Frankfurt's eyes, these users were better off with their original ignorance rather than the lies or bullshit they found online. Furthermore as Africa is a continent where there are very few protections for digital privacy and laws about freedom of online expression, it has become a concern of many governments that Facebook is exploiting Africa’s lack of technical literacy to drive their business and profits. After failed efforts in Myanmar to protect users safety online, Facebook wrote that they were initially too “idealistic” in their efforts. They claim that moving forward they “have invested in people and technology to build better safeguards,” including fact-checking and support for digital literacy efforts around the globe. <ref> Tiku, Nitasha. After Troubles in Myanmar, Facebook Charges Ahead In Africa. Wired. October 7th 2018. https://www.wired.com/story/after-troubles-myanmar-facebook-charges-ahead-africa/ </ref> |

===Digital Colonialism and Net Neutrality=== | ===Digital Colonialism and Net Neutrality=== | ||

Facebook has also experienced extreme backlash as opponents of Free Basics claim that the movement and services are considered digital colonialism and violate net neutrality. Digital colonialism in this context is the idea that Facebook maintains control over the digital lives of Africa’s population, masking their profit motives as a philanthropic gesture. The content that is viewable with the service is mostly western corporate news and ideologies. Many citizens in Africa have voiced that the articles they find online with Free Basics are not articles that they have any interest in. <ref name=Solon /> In this sense, Facebook has power over the content that billions of users can read, and the content is largely dominated by western ideas revealing an eerie view into the colonial past. | Facebook has also experienced extreme backlash as opponents of Free Basics claim that the movement and services are considered digital colonialism and violate net neutrality. Digital colonialism in this context is the idea that Facebook maintains control over the digital lives of Africa’s population, masking their profit motives as a philanthropic gesture. The content that is viewable with the service is mostly western corporate news and ideologies. Many citizens in Africa have voiced that the articles they find online with Free Basics are not articles that they have any interest in. <ref name=Solon /> In this sense, Facebook has power over the content that billions of users can read, and the content is largely dominated by western ideas revealing an eerie view into the colonial past. | ||

Revision as of 20:29, 29 March 2019

Contents

Free Basics

History

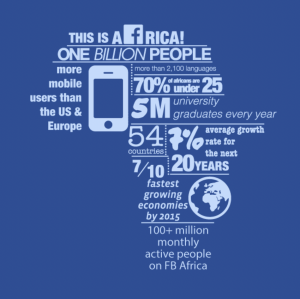

Free Basics is a Facebook-developed mobile application which gives users in Africa a glimpse at internet access. Free Basics, originally named Internet.org was launched in 2013 with the purpose to give affordable internet access to selected less developed countries. [3] It was founded with the idea that Africa's growing cell phone ownership along with internet accessibility lying around 15.5% on the continent provided Facebook with a unique opportunity to "bridge the accessibility gap." [4].

Free Basics provides a set of websites free of mobile data charges that users can access. These websites are often stripped of photos and videos, only leaving plain text behind. [5] The services offered included Facebook itself, news sites, health information, and job search sites. The access was extremely limited and restricted to websites that would allow the population of Africa to generally make more informed decisions about their lives. However with the introduction of the internet to billions of people comes many controversies.

Controversies

Online Behavior

Facebook and internet users in Africa have significantly less experience than users in America - with this comes the need to teach about digital etiquette. The idea of privacy, information transparency, fake news, digital embodiment are all foreign concepts to early internet users. The initial purpose according to Zuckerberg was to offer users “the opportunity to access news, health information and services for free.”[6] Zuckerberg himself believes that access to the internet is among our basic human rights, and that this access has the power to lift people out of poverty. [7] While this may have been Zuckerberg's intentions, the reality is that user's are not receiving or searching for the information they need. Instead, users are considered passive consumers: Free Basics only offers them a small portion of information due to the restriction on sites provided by the service. When searching news, users will react to articles with clickbait headlines and not be able to fully sift through the news topic and obtain a well rounded view of the issue. For these types of users, fake news becomes a monumentous issue in Africa. As Frankfurt stated in his article “On Truth, Lies, and Bullshit” a lie is “designed to prevent us from being in touch with what is really going on.” [8] In this sense, Free Basics’s goal of providing clarity, information, and accessibility to a huge population of people can often backfire by causing users who are extremely uneducated in spotting fake news to believe falsities rather than find answers to news or health questions. In Frankfurt's eyes, these users were better off with their original ignorance rather than the lies or bullshit they found online. Furthermore as Africa is a continent where there are very few protections for digital privacy and laws about freedom of online expression, it has become a concern of many governments that Facebook is exploiting Africa’s lack of technical literacy to drive their business and profits. After failed efforts in Myanmar to protect users safety online, Facebook wrote that they were initially too “idealistic” in their efforts. They claim that moving forward they “have invested in people and technology to build better safeguards,” including fact-checking and support for digital literacy efforts around the globe. [9]

Digital Colonialism and Net Neutrality

Facebook has also experienced extreme backlash as opponents of Free Basics claim that the movement and services are considered digital colonialism and violate net neutrality. Digital colonialism in this context is the idea that Facebook maintains control over the digital lives of Africa’s population, masking their profit motives as a philanthropic gesture. The content that is viewable with the service is mostly western corporate news and ideologies. Many citizens in Africa have voiced that the articles they find online with Free Basics are not articles that they have any interest in. [5] In this sense, Facebook has power over the content that billions of users can read, and the content is largely dominated by western ideas revealing an eerie view into the colonial past.

Facebook has also been criticized for violating net neutrality, which is the principle that internet service providers should treat all users, content, and websites equally. [10]Net neutrality is an often debated subject as some people believe that large technology companies should be allowed to charge different prices for their content or for faster speeds, while many disagree. In India specifically, Facebook faced backlash in regards to violating net neutrality. Activists believed that Free Basics was charging different prices for sites - some were free and some were on a "premium" package. [11] Facebook has been accused of following the “freemium to premium” model as they introduced this free internet service to customers around the continent of Africa and then plan to offer premium services for increased access. The debate in India ended in 2016 when India's telecom regulator banned the differential pricing tactics of Free Basics stating that this tactic was allowing Facebook to determine the population's interaction with the internet and therefore obtaining too much power and control over user's internet experiences. A similar story is expected to happen in some parts of Africa if Facebook does not address these concerns.

Future of Facebook

While Facebook faces many obstacles and controversies in its seemingly altruistic initiatives in Africa, there are some many ways in which these obstacles are inevitable. Since Facebook is offering a limited option of sites for user's to view, and the company is ultimately deciding what is most important for the population, Facebook's views and preferences will automatically be implanted in user's experiences with the internet. Although the African continent struggles from lack of access to health and educational news, it is inevitable that the content they are exposed to is filtered through the view of what Facebook considers most important for the population rather than what they believe is most important. Ultimately, Facebook will receive backlash for these ideas but many of these complications are unavoidable by nature.

See Also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Shapshak, Toby. Almost All of Facebook’s 139 Million users in Africa Are On Mobile. Forbes. December 18th 2018. https://www.forbes.com/sites/tobyshapshak/2018/12/18/almost-all-of-facebooks-139m-users-in-africa-are-on-mobile/#3ab2bd5d68e7.

- ↑ The Economist. In much of sub-Sahran Africa, mobile phones are more common than access to electricity. November 8, 2017. https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2017/11/08/in-much-of-sub-saharan-africa-mobile-phones-are-more-common-than-access-to-electricity

- ↑ Free Basics/Internet.org https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Internet.org

- ↑ Siddharth Singh, Vedant Nanda, Rijurekha Sen, Sohaib Ahmad, Satadal Sengupta, Amreesh Phokeer, Zaid Ahmed Farooq, Taslim Arefin Khan, Ponnurangam Kumaraguru, Ihsan Ayyub Qazi, David Choffnes, and Krishna P. Gummadi. 2017. An Empirical Analysis of Facebook’s Free Basics Program. In Proceedings of ACM Sigmetrics conference, Urbana-Champaign,IL, USA, June 05-09, 2017 (SIGMETRICS ’17), 2 pages. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/3078505.3078554 .

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Solon, Olivia. 'It's digital colonialism': how Facebook's free internet service has failed its users. The Guardian. July 27, 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/jul/27/facebook-free-basics-developing-markets.

- ↑ Shearlaw, Maeve. Facebook Lures Africa with free internet – but what is the hidden cost? The Guardian. August 1st 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/aug/01/facebook-free-basics-internet-africa-mark-zuckerberg

- ↑ Hempel, Jessi. “Facebook Renames Its Controversial Internet.org App.” Wired, Conde Nast, 29 June 2017, www.wired.com/2015/09/facebook-renames-controversial-internet-org-app/.

- ↑ Frankfurt, Harry. “On Truth, Lies, and Bullshit.” The Philosophy of Deception, by Clancy W. Martin, Oxford University Press, 2009.

- ↑ Tiku, Nitasha. After Troubles in Myanmar, Facebook Charges Ahead In Africa. Wired. October 7th 2018. https://www.wired.com/story/after-troubles-myanmar-facebook-charges-ahead-africa/

- ↑ Net neutrality https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Net_neutrality

- ↑ Tripuraneni, Hanuman Chowdary. “The Free Basics (of Facebook) Debate in India.” Info, vol. 18, no. 3, 2016, pp. 1–3., doi:10.1108/info-02-2016-0005.