FICO Score

FICO Score is a credit scoring model developed by the data analytics company, FICO (Fair Isaac Corporation). Similar to other credit scoring systems, FICO Score's algorithm uses debt data from an individual's credit report to formulate the score.[2] The score is used as a metric for lenders to determine whether or not an individual is a credit risk or not.[3]FICO is currently the most widely used credit scoring algorithm in The United States of America. FICO 8, the eighth version of the FICO score, is used by the three main credit bureaus in the United States. The three main credit bureaus commonly referred to as "the big three" are Experian, TransUnion, and Equifax. [4]

Contents

FICO

About

FICO is a data analytics company that serves its corporate client base by assisting their business decisions. In addition to their most well-known product FICO Score, the company also has other software tools that are used to improve customer relations and optimize business interactions. Following suit with other Big Data corporations, FICO utilizes technologies such as cloud computing and open-source standards.[5]

FICO operates globally in over 20 countries spanning six continents. The corporation provides solutions in an array of fields such as finance, health care, automotive, telecommunications, and more.[6] [7]

History

Founded in 1956 by engineer Bill Fair and mathematician Earl Isaac with hopes to improve the manner in which businesses make discussions. Two years later, the company released its first credit scoring algorithm. FICO moved its headquarters from San Fransisco, California to San Rafael California in 1961. In 1972 FICO debuted the first automated application processing system at Wells Fargo. FICO revealed another credit scoring model the FICO Credit Bureau Risk Score in 1981. The next year, FICO opens its first international office in Monaco. In 1987 FICO becomes a publicly-traded stock in the New York Stock Exchange. FICO moved its headquarters again to Minneapolis, Minnesota in 2004. In 2013, FICO returned its headquarters to California by moving to San Jose. [9]

Algorithm

History

Credit scoring systems had existed before the FICO Score since the 1800s for use in the commercial space. They were originally developed by lenders to systemize determining whether or not a loan would be a risk or not. These early credit systems included racial, gender, and class information to aid the lending process. In the 1900s, the need for credit scores increased to meet the needs of a growing middle class. To meet this demand, algorithms collected data on individuals' social, political, and sexual lives. In the 1970's, the government passed the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) which disallowed the gathering of demographical data for use in determining credit eligibility. [10] [11]

FICO Score was created in 1989 to fill the need for a standard credit scoring algorithm that was also unbiased. [12] In 1991, FICO Score is used by all three major credit bureaus in The United States. Two years later, FICO designs specialized scores for each type of loan. The most widely used version of the FICO Score, FICO 8, was released in 2009. FICO 8 has a market share of 90% in America. Because of this when most people refer to credit scores they usually are referring to the FICO Score. [13]

Breakdown

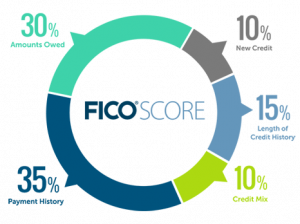

The FICO Score is comprised of five major parts.

Payment history is the largest component and takes up 35 percent of the FICO Score. Particularly, this component focuses on if the individual has made payments. The component also tracks if the payments were made on time. This information includes the history of credit cards, home loans, and car loans. If the individual makes their payments on time their score will be higher.

Amounts owed make up 30 percent of the FICO Score and are based on how much money the individual has actually borrowed in relation to their available credit. Typically, the less available credit an individual borrows the higher their score will be.

The length of credit history makes up 15 percent of the score. The length is determined by taking the individual's average age of credit accounts. The older the average age of accounts the higher the FICO Score will be.

The next 10 percent of the score is based on credit diversity. Credit diversity considers the mix of credit accounts of an individual. Generally, the more variety in types of credit the individual has the higher this portion of the score is.

New credit makes up the final 10 percent of the FICO Score. This portion of the score includes not only new accounts opened by the individual but also accounts that the individual has attempted to open. The fewer new credit lines an individual decides to open it is seen as less of a risk so their score would be higher. [15] [16] [17]

FICO Scores do not include demographics, salaries, or social information. [18]

All information used by the scoring algorithm is pulled from the individual's credit report. [19] Credit reports consist of payment information sent from lenders. This information is kept by credit reporting agencies. Most of the time, credit reports are pulled from "the big three" credit bureaus.

Scoring Range

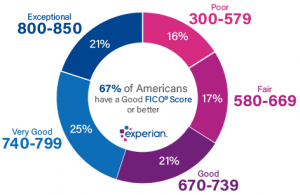

FICO Scores range from 300 to 850 with a higher number representing a better score. The average FICO Score is around 670. FICO defines ranges for scores as <580 is poor, 580-669 is fair, 670-739 is good, 740-799 is very good, and a score 800 or higher is exceptional. Each range represents roughly 20% of all FICO Score users. [21] [22]

Competitor algorithms

While FICO Score has a 90% market share there are other credit scoring algorithms that exist and are in use. The most notable competing algorithm is VantageScore. [23]

Vantage Score

VantageScore was created in 2006 by the three major credit bureaus to improve upon the existing credit scoring models. Another reason VantageScore was developed was to introduce a competitor to FICO Score. VantageScore shares many similarities to FICO Score. Both use the same information to determine their score. VantageScores, like FICO Scores, also range from 300-850. [24] [25] [26]

The newest version of VantageScore, VantageScore 4.0, uses machine learning algorithms in determining its scores. It is the only credit scoring algorithm to do so. [27]

Discrimination concerns

Racial bias

One of the major criticisms of credit scores, in general, is that they are built with an inherent racial bias. Proponents of this belief that the algorithms that are used to determine credit scores have racial bias "baked in" to them. Minority groups are typically negatively impacted by bias. [28] Despite this, designers of modern credit scoring systems say that the purpose of scores was to eliminate all kinds of bias from lending. [29]

A contention used for criticizing racial bias in credit scores is the long history of discrimination against minority groups in America. Lynette Khalfani-Cox co-founder of The Money Coach and New York Times bestselling author says, "From the 1930s to the 1960s, the federal government flat-out refused to insure home loans for Black people. This meant that 98 percent of the loans approved went to White Americans, which created the White middle class.” [30] [31] Congress passed the Fair Housing Act and Equal Credit Opportunity Act in the sixties and seventies. However, the effects of the past policies led to the modern racial wealth, information, and access gaps. FICO Score and other credit scoring algorithms are reflections of these gaps. [32] [33]

The Urban says that racial disparity in FICO Scores are deemed to be caused by ethnic gaps. Furthermore, credit scores can be used to further the racial gaps. Having a lower credit score can hinder a person's ability to obtain a loan, impact the cost of insurance, and decrease the chances of securing housing. [34]

A study by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, conducted in 2012, examined FICO Score variations amongst different racial subgroups. It was discovered that the median FICO Score for zip codes that were mostly inhabited by minorities had were in the 34th percentile of all FICO Scores while not minority-dominated zip codes were in the 51st percentile. [35]

Representatives at FICO say that the models they use to determine credit scores were not developed with any discrimination in mind. From Frederic Huynh of FICO, "I am troubled when I read allegations in the press that FICO® Scores discriminate against people of color. That’s because a credit score is nothing more than the output of a mathematical formula built to rank-order the likelihood that a person will repay the debts they have incurred." [36]

In 2010, the Finance Reserve Board conducted a study to see if credit scoring produces a disparate impact. They described that credit scoring models did not have any proxies for race or ethnicity. The study also stated that distributions of credit scores are mostly unaffected if the scoring models were deployed in an ethnically neutral environment. [37]

Debt discrimination

Employment

According to the Society for Human Resources Management, employers that use debt checks on potential job candidates can filter qualified individuals out of the job. Many employers use credit checks as a barrier to entry for positions in an array of fields. A survey from the Society for Human Resources Management stated that 47% of employers use credit checks on some or all job applicants. [38] From the same survey, it was reported that one in seven applicants said that they had been denied a job due to their credit situation. These credit checks may not take into account the reasoning behind why an individual's credit is not doing so well. This type of discrimination can potentially filter out highly qualified candidates. [39]

The Balance states that employment bias through credit scores can create a cycle of individuals who need a job in order to pay their bills and stay out of debt but cannot get a job to generate any income. [40]

Inaccuracies

A 2013 report from the Federal Trade Commission said that 21% of Americans had an error on their credit report with 13% having errors significant enough to affect their credit score. [41] Lower credit scores as a result of reporting errors can cause consumers to pay more in interest and not qualify for certain loans.

Correcting credit report errors can take a long time according to a New York Times report which tells the story of Maria Ortiz, a woman who found out her credit report had severe errors. Her report showed that she had two cars even though she did not drive and a mortgage despite her not having a house. It took Ortiz to send over 20 letters to businesses and bureaus to fix the issues on her report. Ortiz said, “I did have a lot of credit cards, but I always paid them on time,” she said. “I only had $500 of credit card debt, maybe less, and they weren’t outstanding.” Her credit reputation has since been restored, and she has achieved a nearly perfect TransUnion score, 798, but the blemish on her record took several months to reverse and was not without consequences." [42] [43]

Credit invisibility

The term credit invisibility is used to describe individuals who do not have any credit history or do not have enough history to generate a credit score. The National Consumer Law Center estimates that over 45 million Americans fall into the category of being credit invisible. [44]

Liberty Street Economics states that being credit invisible can make it a lot more difficult to access debt. Since lenders use credit scores to determine loan eligibility those who are credit invisible are either unable to obtain credit or have a longer and more invasive application process. In the case of emergency loans, this means credit invisible people may not be able to get their loans on time. Another effect of being credit invisible is having higher security deposits and interest rates because lenders do not have a solid measure of risk. [45]

A 2015 Consumer Financial Protection Bureau report described that Black and Hispanics were more likely to be credit invisible than their non-ethnic counterparts. Additionally, the report also said that those who came from low-income neighborhoods were also more likely to be credit invisible. [46]

Predicting risk

A popular argument against credit scores is that they are poor predictors of risk. VantageScore says that credit scores are not designed to be absolute predictors of risk but rather the scores can be translated into an estimate of risk. Over time, credit scores can become more and more accurate, but for individuals with short credit history, the scores are more ambiguous as predictors of financial risk. [47]

Medical Debt

Medical debt does not have a direct impact on someone's credit score. Medical debt is handled differently than most other forms of consumer debt as health care providers do not report information to credit reporting agencies. Medical debt only shows up on one's credit report once the debt has been sent to a debt collections agency. After the debt reaches collections there is usually a grace period offered by the credit reporting agencies before it shows up on a credit report. The effects of having unpaid medical debt will have an impact on someone's credit score for seven years. [48]

A Demos survey reported that more than half of respondents with a low credit score said that the cause was due to having large amounts of medical debt. That same study stated that a lack of good health coverage is a leading cause of poor credit. They noted that someone without health coverage was more than twice as likely to report having a declining credit score over the past three years. The study describes that poor credit can be more of a sign of medical misfortune rather than an indicator of risk. [49]

A study by the Commonwealth Fund said that 40% of Americans who struggle to pay off medical debt have noticed a negative impact on their credit score. Furthermore, being in medical debt caused these individuals to have to resort to taking on more debt in an attempt to pay it off. The Study said that over eight million adults had to take out a loan or mortgage their homes in order to pay off their medical debt. Having to take out more debt to pay off existing debt is likely to tank their score more as it reflects negatively in the FICO Scoring algorithm. [50] [51]

Student loan debt

According to the NFCC, student loans can have a positive impact on a credit score. Student loans are seen as a type of installment loan on a credit report which the FICO Score algorithm views as more favorable than other loan types such as revolving credit. At the same time, because the algorithm weighs student loans more heavily, the cost of missing payments and even defaulting can have a drastic impact on a credit score. Once a loan is paid off, consumers will likely see a drop in their score. This is because a FICO favorable form of debt has left their credit report and their credit mix has become less diverse. [52]

Due to the 2020 coronavirus epidemic, the United States Department of Education had paused all student loans. A Federal Reserve Board study had stated that the student loan pause caused the borrower's average credit score to increase from 647 to 656. [53] However, a report from the Urban Institute says that the short-term credit relief the loan pause has brought does not seem to indicate a long-term improvement in borrowers' financial success. The report described the idea that credit scores may not be a good predictor of financial stability. [54]

Morality

The idea of debt has been a topic that has been questioned morally over the course of history. Some cultures view it as a part of nature and others believe it is sinful. [55]

As the world becomes more and more data-driven so too are credit scores and the lenders who use them. Newer versions of FICO Score, such as FICO Score XD, are using big data to help collect information on users and calculate their scores. A report by the International Business School Suzhou says that data collected from this method may be objective the way that the data is classified may be subjective. Furthermore, they say using big data to categorize individuals based on their credit score can lead to people being trapped into certain groups. For example, low-income and minority groups are more likely to have a lower FICO Score than those who are more well off. So, the report describes that individuals in low-income and minority groups will have a much more difficult time trying to fix their credit scores and improve their credit standing. [56]

Transparency

A common criticism against FICO Scores is that FICO does not publicly reveal what goes into its algorithms. All of the FICO algorithms are kept under patent and are well protected. This leads to a lot of concern amongst consumers who wish to know what data is being used to calculate the scores as well as where it is being collected from. [57] FICO does provide information on what factors it uses to calculate its score and how important each factor is. Many credit reporting websites such as Experian and myFICO allow users to view a free version of their credit score. This version of the FICO Score is different than what lenders see during the credit process. [58]

See also

References

- ↑ Fair Isaac Corporation. (2018). Frequently asked questions about FICO scores. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://www.ficoscore.com/ficoscore/pdf/Frequently-Asked-Questions-About-FICO-Scores.pdf

- ↑ Fair Isaac Corporation. (2021, October 27). How are FICO scores calculated? myFICO. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://www.myfico.com/credit-education/whats-in-your-credit-score

- ↑ FINRA. (2015, January 9). How your credit score impacts your financial future. How Your Credit Score Impacts Your Financial Future | FINRA.org. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://www.finra.org/investors/personal-finance/how-your-credit-score-impacts-your-financial-future#:~:text=A%20credit%20score%20is%20usually,the%20time%20of%20your%20application.

- ↑ University of Illinois Credit Union. (2022, January 14). Your credit score is the most important score you should know. U of I Community Credit Union. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://www.uoficreditunion.org/your-credit-score-is-the-most-important-score-you-should-know/

- ↑ Fair Isaac Corporation. (n.d.). About Us. FICO. Retrieved February 8, 2022, from https://www.fico.com/en/about-us

- ↑ Fair Isaac Corporation. (n.d.). About Us. FICO. Retrieved February 8, 2022, from https://www.fico.com/en/about-us

- ↑ Fair Isaac Corporation. (n.d.). Contact us. FICO. Retrieved February 8, 2022, from https://www.fico.com/en/contact-us

- ↑ Fair Isaac Corporation. (2015). From credit scoring to cloud analytics: A video history of Fico. FICO Decisions Blog. Retrieved February 8, 2022, from https://www.fico.com/blogs/credit-scoring-cloud-analytics-video-history-fico

- ↑ Fair Isaac Corporation. (n.d.). FICO history. FICO. Retrieved February 8, 2022, from https://www.fico.com/en/history

- ↑ Rob_Kaufman. (2018, July 25). The history of the FICO® score. myFICO. Retrieved February 8, 2022, from https://www.myfico.com/credit-education/blog/history-of-the-fico-score

- ↑ Fair Isaac Corporation. (n.d.). FICO history. FICO. Retrieved February 8, 2022, from https://www.fico.com/en/history

- ↑ Rob_Kaufman. (2018, July 25). The history of the FICO® score. myFICO. Retrieved February 8, 2022, from https://www.myfico.com/credit-education/blog/history-of-the-fico-score

- ↑ Fair Isaac Corporation. (2014). Learn about the FICO® score and its long history. Home | 25th Anniversary. Retrieved February 8, 2022, from https://www.fico.com/25years/

- ↑ Fair Isaac Corporation. (2021, October 27). How are FICO scores calculated? myFICO. Retrieved February 9, 2022, from https://www.myfico.com/credit-education/whats-in-your-credit-score#:~:text=Your%20FICO%20Score%20is%20calculated%20only%20from%20the%20information%20in,of%20credit%20you%20are%20requesting.

- ↑ Fair Isaac Corporation. (2018). Frequently asked questions about FICO scores. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://www.ficoscore.com/ficoscore/pdf/Frequently-Asked-Questions-About-FICO-Scores.pdf

- ↑ Fair Isaac Corporation. (2014). Learn about the FICO® score and its long history. Home | 25th Anniversary. Retrieved February 8, 2022, from https://www.fico.com/25years/

- ↑ Fair Isaac Corporation. (2021, October 27). How are FICO scores calculated? myFICO. Retrieved February 9, 2022, from https://www.myfico.com/credit-education/whats-in-your-credit-score#:~:text=Your%20FICO%20Score%20is%20calculated%20only%20from%20the%20information%20in,of%20credit%20you%20are%20requesting.

- ↑ Fair Isaac Corporation. (2018). Frequently asked questions about FICO scores. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://www.ficoscore.com/ficoscore/pdf/Frequently-Asked-Questions-About-FICO-Scores.pdf

- ↑ Fair Isaac Corporation. (2021, October 27). How are FICO scores calculated? myFICO. Retrieved February 9, 2022, from https://www.myfico.com/credit-education/whats-in-your-credit-score#:~:text=Your%20FICO%20Score%20is%20calculated%20only%20from%20the%20information%20in,of%20credit%20you%20are%20requesting.

- ↑ Resources.display. (2021, December 7). What is a good credit score? Experian. Retrieved February 9, 2022, from https://www.experian.com/blogs/ask-experian/credit-education/score-basics/what-is-a-good-credit-score/#:~:text=The%20base%20FICO%C2%AE%20Scores,is%20still%20670%20to%20739.

- ↑ Fair Isaac Corporation. (2021, October 21). What is a FICO score and why is it important? myFICO. Retrieved February 9, 2022, from https://www.myfico.com/credit-education/what-is-a-fico-score

- ↑ Resources.display. (2021, December 7). What is a good credit score? Experian. Retrieved February 9, 2022, from https://www.experian.com/blogs/ask-experian/credit-education/score-basics/what-is-a-good-credit-score/#:~:text=The%20base%20FICO%C2%AE%20Scores,is%20still%20670%20to%20739.

- ↑ Fair Isaac Corporation. (n.d.). FICO® scores are used by 90% of top lenders. FICO® Score – The Score that Lenders Use. Retrieved February 9, 2022, from https://www.ficoscore.com/about#:~:text=FICO%20%C2%AE%20Scores%20are%20the,lenders%20use%20FICO%20%C2%AE%20Scores.

- ↑ Resources.display. (2021, December 7). What is a good credit score? Experian. Retrieved February 9, 2022, from https://www.experian.com/blogs/ask-experian/credit-education/score-basics/what-is-a-good-credit-score/#:~:text=The%20base%20FICO%C2%AE%20Scores,is%20still%20670%20to%20739.

- ↑ Steele, J. (2021, September 17). What is a VantageScore credit score? Experian. Retrieved February 9, 2022, from https://www.experian.com/blogs/ask-experian/what-is-a-vantagescore-credit-score/

- ↑ VantageScore. (n.d.). About VantageScore. VantageScore. Retrieved February 9, 2022, from https://vantagescore.com/company/about-vantagescore

- ↑ VantageScore. (n.d.). Our models. VantageScore. Retrieved February 9, 2022, from https://vantagescore.com/lenders/our-models#vantage-score-4

- ↑ https://www.nclc.org/images/pdf/credit_discrimination/Past_Imperfect050616.pdf

- ↑ Holmes, T. E. (2021, November 23). How race affects your credit score. CreditCards.com. Retrieved February 9, 2022, from https://www.creditcards.com/credit-card-news/how-race-affects-your-credit-score/

- ↑ https://www.nclc.org/images/pdf/credit_discrimination/Past_Imperfect050616.pdf

- ↑ Holmes, T. E. (2021, November 23). How race affects your credit score. CreditCards.com. Retrieved February 9, 2022, from https://www.creditcards.com/credit-card-news/how-race-affects-your-credit-score/

- ↑ National Consumer Law Center. (2016, May). Past imperfect: How credit scores and other analytics ... NCLC. Retrieved February 9, 2022, from https://www.nclc.org/images/pdf/credit_discrimination/Past_Imperfect050616.pdf

- ↑ https://www.nclc.org/images/pdf/credit_discrimination/Past_Imperfect050616.pdf

- ↑ Ratcliffe, C., & Brown, S. (2017, November 20). Credit scores perpetuate racial disparities, even in America's most prosperous cities. Urban Institute. Retrieved February 9, 2022, from https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/credit-scores-perpetuate-racial-disparities-even-americas-most-prosperous-cities

- ↑ Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. (2012, September). Analysis of differences between consumer creditor ... Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Retrieved February 9, 2022, from https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201209_Analysis_Differences_Consumer_Credit.pdf

- ↑ Huynh, F. (n.d.). Do credit scores have a disparate impact on racial minorities? FICO Decisions Blog. Retrieved February 9, 2022, from https://www.fico.com/blogs/do-credit-scores-have-disparate-impact-racial-minorities

- ↑ Federal Reserve Board. (2010). Finance and economics discussion series ... - federal reserve. Federal Reserve Board. Retrieved February 9, 2022, from https://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/feds/2010/201058/201058pap.pdf

- ↑ Society for Human Resources Management. (2021, August 19). Research & Surveys. SHRM. Retrieved February 9, 2022, from https://www.shrm.org/hr-today/trends-and-forecasting/research-and-surveys/pages/default.aspx

- ↑ Traub, A. (2014, February 3). Discredited: How employment credit checks keep qualified workers out of a Job. Demos. Retrieved February 10, 2022, from https://www.demos.org/research/discredited-how-employment-credit-checks-keep-qualified-workers-out-job

- ↑ Irby, L. T. (2021, December 29). The major ways losing your job can impact your credit. The Balance. Retrieved February 10, 2022, from https://www.thebalance.com/how-job-loss-can-affect-your-credit-score-960980

- ↑ Federal Trade Commission. (2013). Federal Trade Commission | protecting America's consumers. Federal Trade Commission. Retrieved February 10, 2022, from https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/reports/section-319-fair-and-accurate-credit-transactions-act-2003-fifth-interim-federal-trade-commission/130211factareport.pdf

- ↑ Rebecca White, “A Credit Nightmare, but Coming Out Better in the End,” The New York Times, January 11, 2012.

- ↑ Traub, A. (2014, February 3). Discredited: How employment credit checks keep qualified workers out of a Job. Demos. Retrieved February 10, 2022, from https://www.demos.org/research/discredited-how-employment-credit-checks-keep-qualified-workers-out-job

- ↑ National Consumer Law Center. (2021, February). Issue brief: The credit score pandemic paradox and credit ... National Consumer Law Center. Retrieved February 11, 2022, from https://www.nclc.org/images/pdf/special_projects/covid-19/IB_Pandemic_Paradox_Credit_Invisibility.pdf

- ↑ ankur, P. by: (2021, June 16). A monthly peek into Americans' credit during the covid-19 pandemic. Liberty Street Economics. Retrieved February 11, 2022, from https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2020/08/a-monthly-peek-into-americans-credit-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/

- ↑ Brevoort , K. P. (2015, May). Data Point: Credit Invisibles. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Retrieved February 11, 2022, from https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201505_cfpb_data-point-credit-invisibles.pdf

- ↑ VantageScore. (n.d.). The dynamic relationship between a credit score and risk. VantageScore. Retrieved February 11, 2022, from https://vantagescore.com/pdfs/Credit-Scores-and-Risk-Relationship-WP-FINAL_2020-10-29-021228.pdf

- ↑ Axelton, K. (2020, November 20). How does medical debt affect your credit score? Experian. Retrieved February 11, 2022, from https://www.experian.com/blogs/ask-experian/medical-debt-and-your-credit-score/

- ↑ Traub, A. (2014, February 3). Discredited: How employment credit checks keep qualified workers out of a Job. Demos. Retrieved February 10, 2022, from https://www.demos.org/research/discredited-how-employment-credit-checks-keep-qualified-workers-out-job

- ↑ Doty, M. M. (2008, August). August 2008 issue brief - commonwealth fund. Commonwealth Fund. Retrieved February 11, 2022, from https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/documents/___media_files_publications_issue_brief_2008_aug_seeing_red__the_growing_burden_of_medical_bills_and_debt_faced_by_u_s__families_doty_seeingred_1164_ib_pdf.pdf

- ↑ Axelton, K. (2020, November 20). How does medical debt affect your credit score? Experian. Retrieved February 11, 2022, from https://www.experian.com/blogs/ask-experian/medical-debt-and-your-credit-score/

- ↑ Opperman , M. (2020, August 17). How paying off Student Loan Debt Affects Your Credit Score. NFCC. Retrieved February 11, 2022, from https://www.nfcc.org/resources/blog/student-loans-paying-off-affect-credit-score/

- ↑ ankur, P. by: (2021, June 16). A monthly peek into Americans' credit during the covid-19 pandemic. Liberty Street Economics. Retrieved February 11, 2022, from https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2020/08/a-monthly-peek-into-americans-credit-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/

- ↑ Blagg, K., & Chien, C. (2020, October 6). The student loan pause has improved credit scores, but not financial risk. Urban Institute. Retrieved February 11, 2022, from https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/student-loan-pause-has-improved-credit-scores-not-financial-distress

- ↑ NIKITA AGGARWAL is a research associate at the Oxford Internet Institute’s Digital Ethics Lab. (n.d.). The new morality of debt – IMF F&D. International Monetary Fund - Homepage. Retrieved February 11, 2022, from https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2021/03/new-morality-of-debt-aggarwal.htm

- ↑ Victor Chang and Jing Lin. A Discussion Paper on the Grey Area – The Ethical Problems Related to Big Data Credit Reporting. International Business School Suzhou. Retrieved February 11, 2022, from https://www.scitepress.org/papers/2018/68236/68236.pdf

- ↑ Hennelly, J. (2020, October 3). Credit scores: Transparency and inclusiveness in the banking industry. Fordham Journal of Corporate and Financial Law. Retrieved February 11, 2022, from https://news.law.fordham.edu/jcfl/2020/10/03/credit-scores-transparency-and-inclusiveness-in-the-banking-industry/

- ↑ Fay, B. (2021, December 16). Your credit score: Secret, especially from you. Debt.org. Retrieved February 11, 2022, from https://www.debt.org/blog/your-credit-score-secret-especially-from-you/