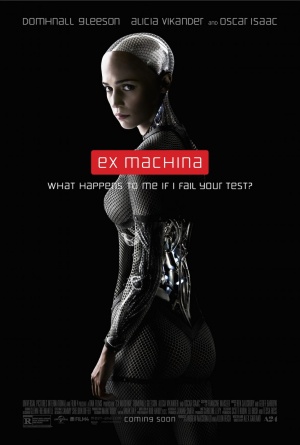

Ex Machina (2014)

Ex Machina (2014) is a science fiction thriller film that explores AI's morality during a one-week visit to a research facility. The film was written and directed by Alex Garland and starred Domhnall Gleeson, Oscar Isaac, and Alicia Vikander. The film's title references the plot device deus ex machina, meaning god from the machine. Ava is the machine reigning supreme at the end after a series of unforeseen circumstances. The film's minimalistic nature isolates their characters and puts their interactions at the front of the viewer's front of the mind. Many ethical conversations surround the film and its concepts, including discourse on morality and relationships with AI, power balance, gender and sexuality, and race. It won an Academy Award for Best Visual Effects and received critical praise.

Contents

Plot

The film begins with the protagonist Caleb Smith winning a contest to spend a week at the secluded estate of the CEO of his internet company, Nathan. At the estate, Caleb is told that he has been chosen to participate in a Turing Test, which determines the human-like characteristic of a robot. The robot in question is a beautiful-faced female robot named Ava. As the days go on, while under strict surveillance by Nathan, Caleb learns about Ava's highest level of consciousness. Soon, Caleb develops feelings for Ava, and the two conspire to go against Nathan, whom Ava has convinced Caleb is untrustworthy.

As Caleb begins to go forth with Ava and his plan, Nathan reveals he was listening in on their private conversations. Additionally, he admits to Caleb the original test was to see if a lustful Caleb could be manipulated by Ava, ultimately testing her intelligence level. As Caleb and Ava continue with a modified version of their plan, Nathan ends up dead after Ava stabs him, and Caleb anticipates escaping the estate with Ava. After she gives her mechanical-self a makeover to become physically more human-like, Ava leaves Caleb trapped in the estate while he screams for help. The film ends with Ava getting picked up by the helicopter scheduled for Caleb’s return home and walking through a city to begin her life as a “human.” [1]

Production

Setting

While the film is set in Alaska, exterior filming took place in Norway's Valldal valley primarily at the Juvet Landscape Hotel. [2] The hotel was selected by production designer Mark Digby and art director Michelle Day as a symbol of "symbiosis between nature and man-made technology." [3] Interior filming took place at Pinewood Studios in England. [3] The main interior setting in the film is the research facility and home of Nathan (Oscar Isaac) and his AI. The sets in Pinewood were built with 15,000 mini-tungsten pea bulb lights to avoid the typical fluorescent light seen in science-fiction films.[3] The lights also added an "emotional warmth" to the set and were easy to change which supported the rapid filming schedule.[3]

Visual Effects

The film features the artificially intelligent humanoid robot, Ava, who is built with a combination of realistic, metallic, and translucent pieces. The design came about from the art department and DNEG.[4] While designing Ava, the team was forbidden from looking at robots but was allowed to study anatomy, Formula 1 suspension and high-end bikes.[4] The team also worked with references images of modernist sculptures by Constantin Brâncuși.[5] The film did not use green screens due to its 6 week filming schedule and to maintain the right "mood". [6] Instead, every take was shot once without Ava and another with her so the background could be edited in. [5] The actress, Alicia Vikander, was also scanned separately to build her CG model both with and without her final costume. [4] Her feet, hands, and face were photographic in 99% of the shots, while the rest of her body was edited [5] Her torso, arms, and legs were edited to look translucent with plastic ribbons and metal pieces showing through. [4] These parts were rendered using DNEG's physically plausible rendering pipeline and supplemented with shaders to make the metallic materials look most realistic. [4] In a scene in which Ava puts on clothing, it was necessary to add CG clothing that was visible through transparent sections of her body. [6]

Robot Rights

Strides in the evolution of robotics have made the notion of robot rights the topic of many debates. The movie Ex Machina brings up the question of "what rights will sentient robots have?" Although it is currently relevant, this topic is not new and was discussed in the 1964 paper titled "Robots: Machines or Artificially Created Life?" [8] The author of this paper, Hilary Putnam, takes a deep dive into the ethical implications of sentient robots, such as Ava, the film's protagonist, with a series of thought experiments. In Japan, you can find the first robot to have a Koseki, comparable to a birth certificate in the United States, which provides the basis for citizenship and subsequent rights. The robot is Paro, the therapeutic, robotic baby seal. [9] Then, in 2017, the very first robot in history got citizenship status in Saudi Arabia. The robot's name is Sophia and was created by Hanson Robotics with the features of a chatbot.

Robot ethics take into account the principles established when building and using robots to ensure moral standards are being met whether you consider a non-biological entity alive or not. Today's robots employ the master-slave paradigm where no independence of action beyond direct human violation is permitted. Ex Machina imagines a situation where artificial intelligence has surpassed this paradigm and shows the importance of questions concerning responsibility. David J. Gunkel analyzes this question with his paper entitled: "Robots can have rights; Robots should have rights," which visits a time when robots become moral subjects and break free from the limitations of being a mere machine. [10] Robot's moral standing is two-sided: one side states in the distant future, robots will qualify for rights, and the other side rejecting that possibility. A properties-based approach will consider how we treat a robot, depends on its characteristics. [11] If the robot can fulfill responsibilities to do something benefiting others, the robot will meet the criteria to be considered alive and therefore eligible to have rights. On the other hand, if it is true robots cannot possess consciousness, they would be ineligible for the legal/civil rights we have as humans.

In addition to consciousness, experts consider the implications of robots on human rights and welfare. Abeba Berhane writes that "the integration of these systems is proving to be a threat to people’s welfare, integrity and privacy, especially those socioeconomically disadvantaged"[12] The debate around robots does and will continue to include their standing in society. It is suggested by some that robots could be used as a sort of slave labor. There is a narrative historical background for this idea that can be found as far back as “R.U.R.” (“Rossum’s Universal Robots”) which were part of a science fiction play a century ago, in 1921.[13] Ex Machina (2014) takes the idea of AI as slaves and grapples with it. Nathan utilizes all of his previous iterations of female AI as slaves for either housework or sex, meanwhile, Caleb is unaware of this. Upon discovering they are slaves, he is disgusted. These two characters work in a binary to tell the viewer that there are opposing sides to this debate around AI rights.

Ethical Issues

Ex Machina's (2014) premise revolves around whether or not Ava can pass the Turing test[14] – an AI convincing a human that it is also a person and can think. Ava is the nth iteration of AI, showing the most promising results in this film. Unlike a typical Turing test, Ava is in full view of the tester (Caleb) and resembles a human woman. Ava's appearance and visibility complicate the test and lead the viewer to ask questions about this technology and the situation's morality.

Morality: how do we treat a sentient AI?

This issue is separate from the issue of AI rights, in that it concerns how we should AI be treated at a human level. Assuming an AI has passed the Turing test and is said to have feelings, what implications does that have on their place in society? We must consider whether they believe themselves to be human.[15] This belief in themselves suggests we should treat them the same way we might treat any other human in our interactions with them. We should practice kindness and involve them in the social aspect of society. They deserve to feel okay the same way we as humans do. However, legality is a different conversation. An AI is not biologically similar to humans, cannot reproduce, and cannot ‘die.’[15] This can impact AI’s chances of being considered human. In the film, Nathan, Ava’s creator, believes AI will destroy the human race. His apathy towards the astronomical impact of his creation suggests that we need to be careful. After all, creating a sentient human AI is “the history of gods,” not man.[1] While Nathan treats Ava like a digital assistant or slave, Caleb treats Ava like a human. The duality of this showcases the ways in which humans in the film Ex Machina treat sentient AI.

Relationships with AI: can we fall in love with them?

It seems we are heading towards a future where chatbots and other AI have romantic relationships with humans.[16] Their realness can be comforting, particularly to lonely people. There are levels to these relationships; chatting with your Alexa is different from having a romantic relationship with an AI, as seen in the movie Her (2013). Our tendency to anthropomorphism[17] (capacity to project human characteristics onto non-human animals and inanimate objects) is problematic in this case. Almost definitely, humans are capable of falling in love with an AI. The question becomes, is this okay? As noted in the section above, they are incapable of truly being a human and therefore living a life with you to a usual standard. Our mortality in comparison to their eternal existence does not match particularly well. While the future may hold a place for AI to help humans, their coexistence in our emotional lives is ethically questionable. In Ex Machina, Ava seems to fall for her tester Caleb, and he falls for her. The complications that arise from this suggest that Ava has a higher goal in mind than love. She uses Caleb for personal gain, similar to how humans might use their partner for financial gain. Instead of forming romantic relationships with sentient AI, it might be more ethical to use AI to help humans find better human matches.

AI and Power: should they be capable of killing?

There is always the possibility of AI taking on the negative traits of humans. The fear that they could go rogue and have detrimental impacts on society, people, and the world, is pervasive. There is also the possibility that AI is hidden by corporations already harming humans[18] AI can have power over the rest of us. Moreover, AI is human-made and can hold certain morals and ideals. Will people create AI that hurts other humans, physically or online? If the goal is creating an AI that passes the Turing test, the AI might have the capacity to take on the negative traits of humans. Ex Machina showcases this tragic outcome. Ava encapsulates humanity's negative aspects by trapping or killing every human she knew (only two). The question has to be asked, though: would she have done this had she not been treated terribly by them? Is it an excuse that she was locked up and waiting to “die” when she became evil? Her reaction to this imprisonment might only prove that she was human. We have to decide whether we are okay with creating an AI capable of terrible things, even if they are innately human actions.

Gender and Sexuality: how does it fit into the world of AI?

AI has long been criticized[19] for primarily being female. There are two reasons we suspect AI typically has a female voice or body: service and sex. Women throughout history have been the caregivers and those who perform service roles. Humans are trained to expect assistance from a woman, whether they are children or adults. It should come as no surprise that our virtual assistants were assigned a feminine voice and role in our lives, providing things for us. However small this decision may seem, it sends a new message of female objectification.[20] This objectification impacts the role of AI and their sexuality. Famously, Sofia the robot is a woman and has been sexualized.[21] It has been proven time and time again that a female AI has to "demonstrate her consciousness/intelligence in a form and with a sensuality" that other male AI don't have to. For example, David from the film Prometheus (2012) never acted in ways that Ava did.[22] The idea that we may form relationships with these robots and the fact that we are primarily creating female AI furthers the objectification of women. Ex Machina depicts both of these suggested realities with clarity. Nathan, the creator, specifically made the machines able to have sex. He found this to be a relevant characteristic of humans, but he speaks about his robots in extremely crude terms. It is suggested, and somewhat shown, he even uses the machines for this purpose. It is even more apparent that he uses all of his previous iterations of AI as housekeepers. One of them is used daily while the rest are held in cabinets in his room. This overemphasized depiction of using the female AIs for service and sex shows where the real world is heading with AI.

Ex Machina and race

As Asian countries have become significant economic players, the depiction of Asian people in popular western media has changed. There has been a focus on Techno-Orientalism, in that Asian bodies are simultaneously portrayed as technologically infused and disposable. [23] Ex Machina plays into these depictions in how it portrays Kyoko, an Asian housekeeper who is later revealed to be an android, much like Ava. Kyoko plays an integral part in freeing Ava, in that she is killed while helping Ava escape. Kyoko is also depicted in a problematic manner in her role as an android housekeeper, in the sense that domestic helpers are often paid for their gendered and racial identities.[24] Especially as an android, Kyoko only exists to function as a maid. Nathan created her and essentially owns her for her labor; her identity is important. Kyoko’s Asian identity plays into racist stereotypes of women, especially Asian women, and reflects a globalized market in which women of color are frequently exploited.[25]

Moreover, Ava using Kyoko’s past skin near the end of the movie reflects how white women often appropriate Asian women and their products for personal gain. [26] Specifically, this is often problematic because Asian women must be removed and are exploited in the process. Ava would potentially face Kyoko's criticism picking out and putting on Kyoko’s skin, so Kyoko’s death was a necessary event leading to Ava’s final escape. Specifically, “we see the dependency of white female empowerment on the disposition of Asian bodies.” [27]

This is especially important due to the lack of Asian representation in film and media. Such irresponsible representations can heavily influence existing stereotypes, identity development, and how minorities are treated. [28] Moreover, because the media is influential, it makes representation even more important, especially in a critically acclaimed film such as Ex Machina.[29]

Critical and Audience Response

The 2014 film received very positive reviews after its release. On the Rotten Tomatoes Tomatometer, it scored a 92% from its 281 reviews. [1] Additionally, Matt Zoller Seitz of the Roger Ebert review site provided a very positive response to the movie. “Throughout, Garland builds tension slowly and carefully without ever letting the pace slacken. And he proves to have a precise but bold eye for composition...Garland’s screenplay is equally impressive, weaving references to mythology, history, physics, and visual art into casual conversations.” [30] Speaking about the actors behind Caleb (Domhnall Gleeson) and Ava (Alicia Vikander), Guy Lodge of Variety states, “Both actors turn in remarkably disciplined work, articulating a burgeoning romance in which the boundary between real and simulated feeling is kept teasingly ambiguous throughout” [31]. On the other hand, there were a few unfavorable reviews of the film. Mark Jenkins of NPR writes, “Reasonably diverting until its predictable (and predictably misogynistic) outcome” [32]. Overall, the film was mostly perceived as being a well-crafted and enjoyable film.

One of the most dominant film social media platforms, Letterboxd, reveals the way people have been interacting with this Ex Machina (2014). One user writes "i fell in love with a sexy robot??? NOT clickbait" further pushing the idea that the AI in the film created for a sexualized gaze.[33] Another user more crically analyzes the film saying "This is a movie about the ways that men treat women. The "Obvious Misogynist" considers women as a tool for him to control and fuck at his leisure. The "Nice Guy" wants to be a friend and liberator to women, but that interest comes and goes proportional to how much he wants to have sex with them. No matter how similar in intellect and skill we prove ourselves to be, they believe it is up to them to determine our worth, our freedom, even our personhood." This recognition of the film's themes and their alignment with the way actual woman are treated stands to say that the main character insulted and upset the audience.[34]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Garland, A. (Director). (2014). Ex Machina [Motion picture]. United Kingdom: Universal Studios.

- ↑ Topping, C. (2015, February 2). Norway: 'ex machina' puts the Valldal Valley in focus. Retrieved April 16, 2021, from https://www.independent.co.uk/travel/europe/norway-ex-machina-puts-valldal-valley-focus-10018274.html>

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Saito, B. (2015, April 13). Intelligent Artifice: Alex Garland's smart, Stylish ex machina. Retrieved April 16, 2021, from https://www.moviemaker.com/intelligent-artifice-alex-garlands-smart-stylish-ex-machina/

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Failes, I. (2015, April 09). Ex Machina: The making of Ava. Retrieved April 16, 2021, from https://www.fxguide.com/fxfeatured/ex-machina-the-making-of-ava/

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Bishop, B. (2015, May 08). More human than human: The making of Ex Machina's INCREDIBLE ROBOT. Retrieved April 16, 2021, from https://www.theverge.com/2015/5/8/8572317/ex-machina-movie-visual-effects-interview-robot-ava

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Khan, F. (2016, February 26). Why ex machina's visual effects will stun you in their simplicity. Retrieved April 16, 2021, from https://www.techradar.com/news/home-cinema/why-ex-machina-s-visual-effects-will-stun-you-in-their-simplicity-1315888/2

- ↑ “Sophia.” Hanson Robotics, 1 Sept. 2020, https://www.hansonrobotics.com/sophia/.

- ↑ Putman, H., & Putnam, H. (1964). Robots: Machines or Artificially Created Life? The Journal of Philosophy, 61(21), 668-691.

- ↑ Jennifer Robertson (2014) HUMAN RIGHTS VS. ROBOT RIGHTS: Forecasts from Japan, Critical Asian Studies, 46:4, 571-598.

- ↑ Gunkel, David J. (2018). 3 S1→S2: Robots Can Have Rights; Robots Should Have Rights. Robot Rights, The MIT Press. MIT Press.

- ↑ Gellers, Joshua C. (2020). Rights for Robots : Artificial Intelligence, Animal and Environmental Law (Edition 1). Routledge.

- ↑ Abeba Birhane and Jelle van Dijk. 2020. Robot Rights? Let's Talk about Human Welfare Instead. In Proceedings of the AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society (AIES '20). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 207–213

- ↑ Beth Singler Research Associate. “AI Slaves: the Questionable Desire Shaping Our Idea of Technological Progress.” The Conversation, 18 Jan. 2021, https://theconversation.com/ai-slaves-the-questionable-desire-shaping-our-idea-of-technological-progress-92487.

- ↑ Oppy, Graham, and David Dowe, "The Turing Test", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2020 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.),<https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2020/entries/turing-test/>.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Peng, Jessica. “How Human Is AI and Should AI Be Granted Rights?” Jessica Peng, 4 Dec. 2018, https://blogs.cuit.columbia.edu/jp3864/2018/12/04/how-human-is-ai-and-should-ai-be-granted-rights/.

- ↑ Morris, Natalie. “Forming Romantic and Sexual Relations with Robots 'Will Be Widespread by 2050'.” Metro, 28 May 2019, https://metro.co.uk/2019/05/28/forming-romantic-and-sexual-relationships-with-robots-will-be-widespread-by-2050-9628364/.

- ↑ “Anthropomorphism.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., https://www.britannica.com/topic/anthropomorphism/.

- ↑ Greene, Tristan. “Neural's Guide to the Glorious Future of AI: Here's How Machines Become Sentient.” Neural | The Next Web, 18 Nov. 2020, https://thenextweb.com/neural/2020/11/18/neurals-guide-to-the-glorious-future-of-ai-heres-how-machines-become-sentient/.

- ↑ Nickelsburg, Monica. “Why Is AI Female? How Our Ideas about Sex and Service Influence the Personalities We Give Machines.” GeekWire, 27 Nov. 2017, https://www.geekwire.com/2016/why-is-ai-female-how-our-ideas-about-sex-and-service-influence-the-personalities-we-give-machines/.

- ↑ Nickelsburg, Monica. “Why Is AI Female? How Our Ideas about Sex and Service Influence the Personalities We Give Machines.” GeekWire, 27 Nov. 2017, https://www.geekwire.com/2016/why-is-ai-female-how-our-ideas-about-sex-and-service-influence-the-personalities-we-give-machines/.

- ↑ Written by Pascale Fung, Professor of Electronic and Computer Engineering. “This Is Why AI Has a Gender Problem.” World Economic Forum, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/06/this-is-why-ai-has-a-gender-problem/.

- ↑ Watercutter, Angela. “Ex Machina Has a Serious Fembot Problem.” Wired, Conde Nast, https://www.wired.com/2015/04/ex-machina-turing-bechdel-test/.

- ↑ Roh, D., Huang, B. & Niu, G. (2015). Technologizing Orientalism: An Introduction. In D. Roh, B. Huang & G. Niu (Ed.), Techno-Orientalism (pp. 1-20). Ithaca, NY: Rutgers University Press. https://doi.org/10.36019/9780813570655-002

- ↑ Tadiar, N. (2004). Fantasy Production: Sexual Economies and Other Philippine Consequences for the New World Order. Hong Kong University Press. Retrieved March 31, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt2jc3j9

- ↑ Parreñas, R. S. (2015). Servants of globalization: Migration and domestic work. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- ↑ Yoshihara, M. (2003). Embracing the East: White women and American orientalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Nishime, L. (2017). Whitewashing Yellow Futures in Ex Machina, Cloud Atlas, and Advantageous: Gender, Labor, and Technology in Sci-fi Film. Journal of Asian American Studies 20(1), 29-49.

- ↑ Tiffany Besana, Dalal Katsiaficas & Aerika Brittian Loyd (2019) Asian American Media Representation: A Film Analysis and Implications for Identity Development, Research in Human Development, 16:3-4, 201-225.

- ↑ Fürsich, E. (2010), Media and the representation of Others. International Social Science Journal, 61: 113-130. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2451.2010.01751.x

- ↑ Seitz, M. Z. (2015, April 9). Ex Machina movie review & film summary (2015): Roger Ebert. movie review & film summary (2015) | Roger Ebert. https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/ex-machina-2015.

- ↑ Lodge, G. (2015, January 16). Film Review: 'Ex Machina'. Variety. https://variety.com/2015/film/global/film-review-ex-machina-1201405717/

- ↑ Jenkins, M. (2015, April 9). Listening To The Ho-Hum Of The Machine. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2015/04/09/398130823/listening-to-the-ho-hum-of-the-machine?utm_medium=RSS&utm_campaign=movies.

- ↑ “Ex Machina (2014).” Ex Machina (2014) Directed by Alex Garland • Reviews, Film + Cast • Letterboxd, https://letterboxd.com/film/ex-machina-2014/.

- ↑ “Ex Machina (2014).” Ex Machina (2014) Directed by Alex Garland • Reviews, Film + Cast • Letterboxd, https://letterboxd.com/film/ex-machina-2014/.