Cyberstalking

Cyberstalking is the use of the Internet and other forms of online and computer technologies to stalk, harass, or threaten a person, group or organization. The action of cyberstalking can include, but is not limited to, threatening behavior, unwanted advances, monitoring, identity theft, soliciting sex to minors and the gathering of personal information without consent. In all cases, the victim(s) can be aware or not aware that such activities are occurring. Cyberstalking can also be accompanied by or lead to in-person stalking and can result in severe injury, emotional trauma, and even the death of the victim(s) involved. Some of the emotional trauma may include humiliating, controlling, frightening, manipulating, embarrassing, getting revenge at, or otherwise harming the victim. [1]

Contents

Background

Cyberstalking has become more prevalent with the rise of certain technologies and the development of digital habits. Contributing the most to this issue are the mass digitization of personal information and commonplace use of virtual communication. Cyberstalking refers to the idea of someone(s) using the internet to gather private information of another person or to track their Internet activity and extrapolate various details of their targets life. They may not know the person they are stalking, but in the case that it is, they may not necessarily involve contacting the victim at all. However, most of the time cyberstalking includes sending unwanted, threatening, or obscene email, posting obscene or threatening messages in discussions or forums. Cyberstalking can be harmful to victims and can potentially cause them death and other related injuries.

If they do not know their victim, then they can find their targets through social media, chatrooms, discussion threads and many other methods online. Some people believe that more and more people are getting involved invost cyberstalking due to the ease of anonymity. Some of these people would not have engaged in offline stalking for fear of being caught.[2]

Who is involved

Perpetrators

The characteristics of a cyberstalker are not limited to a set range of personality of physical traits. Cyberstalking can involve any different combinations of people be they strangers or acquaintances. Cybercrime researchers Leroy McFarlane and Paul Bocij [3] have come to officially recognize five types of cyberstalkers:

- The Rejected Stalker had an relationship with the victim at some point, either romantically or as a friend or family member. They are motivated by seeking both revenge and reconciliation.

- The Intimacy Seeker tries to achieve a relationship with the victim who has peaked their interest and whom they might have mistakenly believed to think returns that interest.

- The Incompetent Suitor wants to develop a relationship but cannot seem to do so within the normal social rules of courtship. They are often intellectually and/or socially incompetent.

- The Resentful Stalker wants to payback their victim for some supposed injury or humiliation they have caused.

- The Predatory Stalker gathers information for the purposes of preparing for an attack.

Victims

Anybody can be a victim of cyberstalking. In a recent study about cyberstalking victims, over 82% of the respondents claimed that they had experienced cyberstalking in some form or another [4]. It is difficult to keep track of and gather on the amount of people who claim to have been stalked online since in most situations, many victims are not completely aware as to whether someone is constantly monitoring them. Common types of victims include but are not limited to women, children and teenagers, or past/present intimate partners.

Ethical implications

There is much debate on whether cyberstalking is considered unique to in-person stalking, or if it is just under the umbrella term of stalking regardless of in what context the stalking was taking place—online or offline.

Universal Public Morality

It is unclear what exactly constitutes moral harm in cyberspace, and when it occurs. There is also debate as to whether it is the players rights who are infringed upon or if the violation is limited to their avatars in the online space. The uniqueness debate is also called into question. In the case of cyberstalking, traditionalists would argue that stalking is stalking regardless of if it was done online or offline, while philosophers would argue that there are some aspects of cyberstalking that are unique, and that the new scope at which stalking can now be carried out online and the ease at which personal information can now be found online constitutes a need for new regulations and considerations [5].

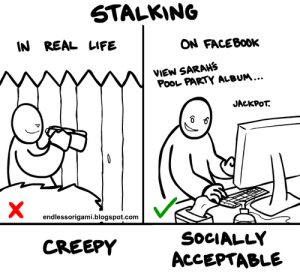

The ease with which "stalking", a type of antisocial networking, has been incorporated as an acceptable activity for users on various social media sites (specifically Facebook) has raised the question whether ethical norms have been changed in the online environment.

Victim Blaming

A good deal of the information posted online is done so voluntarily by the victim of cyberstalking. It is argued that the people who posted the content are consenting to the information being seen and shared by anyone who has access to it. This brings up a multitude of people who could be blamed for any threats or other harm that results from cyberstalking. The victim could be blamed for sharing the information online, but the people who shared it past the victim sharing it online could also be blamed if something malicious happens with the information. In the case of Karen Owen[6], the victim sent an email to a few close friends that contained a PowerPoint with explicit details about her sexual encounters with male students at Duke University. One person forwarded the PowerPoint, and it didn't take long for something that was only meant for a few sets of eyes to go viral. It is still unclear who is at fault for the backlash that Karen Owen had to face, because of the many people involved with the process of making the PowerPoint go viral. This issue compounds itself with the ability to share content easily to a large audience on social media and other forms of communication.

For more information see, Uniqueness of Computer Ethics and Uniqueness Debate.

Doxing

Main Article: Doxxing

Doxxing is the internet-based practice of researching and distributing personally identifiable information of an individual or an organization. The term is commonly used to refer to the exposure of an individual's physical identity through an evidenced connection with a virtual identity, which would otherwise remain anonymous. While not inherently malicious, doxxing may be performed with or without the consent of the individual or organization whose information is released. Agents performing an act of doxxing are known as "doxxers." In regards to cyberstalking, the victim's privacy may be breached through personally identifiable information uncovered by the cyberstalker. Such instances where the cyberstalker finds personally identifiable information from a victim's online identity raises ethical concerns surrounding privacy, anonymity, and virtual identity.

Doxxing groups such as Anonymous[7] have claimed that their attacks directed on groups such as the KKK and terrorist organizations are to promote social good and they should not receive backlash for these attacks. Their main guiding principle is "anti-oppression."[7]

The New Surveillance

Cyberstalking and the law

The US Federal Anti-Cyberstalking laws include 47 USC 223, 18 USC 2261A and the Violence Against Women Act, pertain to any cyberstalking cases crossing state lines. Otherwise, state cyberstalking laws are considered.

However, not every state has a specific cyberstalking law. The National Conference of State Legislatures keeps a complete list on which states have cyberstalking, cyberharassment, and or cyberbullying laws [8].

Examples of cyberstalking cases

Amy Boyer

- Main articles: The Amy Boyer Case.

Amy Boyer, 21, was murdered in October 1999 by Liam Youens who had stalked her online. Youens used the Internet to find personal and confidential information out about Boyer, such as where she lived, where she worked, and what type of car she drove. He even went so far as to obtain her Social Security number through an agent.[9] Youens also created two websites concerning her: one site detailed Boyer's personal information and the other detailed his plans to murder her [5].

Joelle Ligon

Joelle Ligon was cyberstalked for six years by James Murphy, an ex-boyfriend. Murphy sent Ligo emails from alias email accounts that started out as unwanted and later turned pornographic. Murphy also posted Ligon’s phone number in discussion threads and chatrooms that led to Ligon getting phone calls from men asking for sex. During the time cyberstalking was not yet outlawed in Washington State, where Ligon lived and worked, so the police said there was nothing they could do. Ligon then sought help from the FBI. After a long process, Murphy plead guilty to two counts of Internet harassment [10].

Jayne Hitchcock

The Jayne Hitchcock incident is a case of corporate cyberstalking in which Hitchcock, a writer, claimed to be cyberstalked by a manager at Woodside Literary Agency for a number of years. [11] Jayne Hitchcock later went on to become the president of an organization to halt cyberstalking. [12]

United States v. Petrovic

Jovica Petrovic was convicted of four counts of interstate stalking and two counts of interstate extortionate threats after he storing intimate information on his ex wife including sex tapes, nude photos, personal text messages, etc. She attempted to commit suicide in 2009. That December she broke up with Petrovic over text and he informed her of all of the things he had been saving and threatened to post it all on the internet for her family to see if she did not remain in the relationship. In court, he argued that the interstate stalking statute violated his right to freedom of speech. This motion was denied as it was concluded that the non-speech elements of this case took interest over just the speech elements. [13]

Elonis vs US

In 2010, Anthony Elonis was charged with five counts of violating an anti-threat statute. [14] He threatened many people in his life on his Facebook page by posting violent images and graphics as to what he wishes he could do to them. All of the posts were considered threats by the Supreme Court. He claimed that his comments were just a form of him expressing himself through art and rapping and attempted to dismiss the case. However, the court denied his request and he was convicted of four out of five of the counts. [15]

Preventing cyberstalking

There are many different ways to prevent cyberstalking from occurring: [16]

- Do not share private information, such as your name, birthdate, address, or social security number, in a public online space or with someone you do not know.

- Be very careful when interacting with others online whom you have not met before. While your interactions may seem safe, you may be talking to someone who is misrepresenting themselves.

- Do not put your credit card information or any other form of online payment into an unsecured system. While the site may look legitimate, it may in reality be a farce.

- Change your passwords semi-regularly so as to keep your accounts as secure as possible. When creating your passwords, do not use your birthdate, dog's name, or any other piece of information that is relatively easy to find.

- If you believe you are being cyberstalked, do not hesitate to contact the authorities. Save all conversations, transactions, and engagements with your stalker as they will be important for finding the stalker.

In popular culture

- Cyberstalker (2012) starring Mischa Barton, depicts the online harassment and stalking of a woman over the course of several years. [17]

- MTV's Eye Candy, a television show about a blogger targeted by a cyberstalker, premiered in 2013 and was not renewed after one season.[18]

Freeform, formerly ABC Family’s, 7 season long show, Pretty Little Liars, [19] focused on the lives of teenagers as they face a cyberstalker that torments them into their early adult lives. The main victims, a group of five females, often receive threatening messages or emails that blackmailed them to do certain things. The cyber stalker, named “A”, remained anonymous, yet seems to know everything about the girls’ lives. A knew where they all lived, and in some plotlines, A had bugged the girls’ houses. Often times the end credits of each episode would show A hiding behind a bush taping somebody or looking at a video of one of the girls on their laptop. A is a resentful stalker as their main goal was to seek revenge on the characters.

In the popular CW show, One Tree Hill [20], main character, Peyton Sawyer deals with a cyberstalker in the fourth season. Peyton created podcasts narrating her life story, which she would publish online. Her cyberstalker discovered her online and became obsessed with her, meeting her under the false pretense that he was her estranged brother, which at that time, she was in search for. In the end it is revealed that he had been watching Peyton’s podcasts for years and had slowly developed an obsession for her because of her resemblance to his dead ex-girlfriend, serving as a surrogate for him.

See Also

External links

- Cyberstalking - Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

- The National Center for Victims of Crime - Cyberstalking

- U.S. Code - 47 USC Sec. 223

- U.S. Code - 18 USC Sec. 2261A

- Violence Against Women and Department of Justice Reauthorization Act of 2005

References

- ↑ Psychology Today "Cyberstalking: The Fastest Growing Crime" https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/sex-lies-trauma/201503/cyberstalking-the-fastest-growing-crime

- ↑ Privacy Rights Clearinghouse "ONLINE HARASSMENT & CYBERSTALKING" https://www.privacyrights.org/consumer-guides/online-harassment-cyberstalking

- ↑ McFarlane, L. An exploration of predatory behaviour in cyberspace: towards a typology of cyberstalkers. First Monday 8.9 01 Sep 2003: unknown-unknown. University of Illinois, Chicago, in cooperation with the University Library.

- ↑ Bocji, P. Victims of cyberstalking: an exploratory study of harassment perpetrated via the Internet. First Monday 8.10 01 Oct 2003: unknown-unknown. University of Illinois, Chicago, in cooperation with the University Library.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Tavani, Herman T. The uniqueness debate in computer ethics: What exactly is at issue, and why does it matter?. Ethics and information technology 4.1 01 Mar 2002: 37-54. Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- ↑ "2010 Duke University faux sex thesis controversy" https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2010_Duke_University_faux_sex_thesis_controversy

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Sands, Geneva What to Know About the Worldwide Hacker Group ‘Anonymous’ 4.1 01 Mar 09 2016: http://abcnews.go.com/US/worldwide-hacker-group-anonymous/story?id=37761302

- ↑ "Cyberstalking, Cyberharassment and Cyberbullying Laws." NCSL Home. 26 Jan. 2011. Web. <http://www.ncsl.org/default.aspx?tabid=13495>.

- ↑ E. (Ed.). (2006, June 15). The Amy Boyer Case. Retrieved April 19, 2018, from https://epic.org/privacy/boyer/

- ↑ Ho, Vanessa. "Cyberstalker Enters Guilty Plea." Seattle Post. 29 July 2004. Web. <http://www.seattlepi.com/local/article/Cyberstalker-enters-guilty-plea-1150519.php>.

- ↑ Bocij, Paul. Cyberstalking: harassment in the Internet age and how to protect your family. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2004, p. 138.

- ↑ WHO@, Working to Halt Online Abuse

- ↑ United States v. Petrovic, No. 12-1427 (8th Cir. 2012), http://law.justia.com/cases/federal/appellate-courts/ca8/12-1427/12-1427-2012-12-13.html

- ↑ Facts and Case Summary: Elonis v. U.S. http://www.uscourts.gov/educational-resources/educational-activities/facts-and-case-summary-elonis-v-us

- ↑ Facts and Case Summary: Elonis v. U.S. http://www.uscourts.gov/educational-resources/educational-activities/facts-and-case-summary-elonis-v-us

- ↑ "Tips for preventing cyber-stalking", http://www.boston.com/ae/books/gallery/cyber_safety/

- ↑ Cyberstalker (2012), http://www.imdb.com/title/tt2172001/

- ↑ "MTV’s ‘Eye Candy’ Cancelled After One Season", http://deadline.com/2015/04/mtv-technothriller-eye-candy-cancelled-after-single-season-1201412459/

- ↑ King, M. (Producer). (n.d.). Pretty Little Liars [Television program]. Freeform.

- ↑ Schwan, M. (Producer). (2007). One Tree Hill [Television program]. The CW Television Network.